Content warning: discussion of disordered eating and body image issues

I remember being most conscious of my widened hips and my four-inch growth spurt when standing in front of the mirror-lined wall in my gymnasium, practicing full turns and split jumps at gymnastics practice.

I was surrounded by girls who were 5’1” and shorter – thin, lean and graceful. At 5’5”, I felt like a giant. I worried about how much more the vault’s springboard would depress or the uneven bars would buckle down when I put my weight on them compared to my teammates. I worried that my bigger body would magnify mistakes like sickled feet or bent knees when I competed in front of judges.

In seventh grade, I downloaded a calorie counter to my iPod Touch and cut my daily caloric intake in half. For a couple of weeks, I kept up like that, happy to see my (perfectly average) weight drop by a few pounds per week before I became so exhausted and starved that I reverted to my old eating habits.

Dropping a few pounds didn’t help me look more graceful during my routines. In fact, it crippled my abilities. I was moody, lethargic and generally malnourished. I struggled to get through my practices, and I could not give the same attention to minute details like pointed feet and 135 degree kicks that I could on a nutritious diet.

I can’t call my adolescent experiment in weight loss an eating disorder in any diagnosable psychiatric sense, but it certainly exhibited a pattern of disordered eating and body consciousness that I would later learn permeated athletes in what are traditionally categorized as “women’s” sports.

Statistics about the prevalence of eating disorders and body dysmorphia among women in sports are staggering. NEDA, the National Eating Disorder Association, cites that over 50 percent of female athletes in Division 1 NCAA sports reported behaviors that placed them at risk for bulimia. Over one-third reported symptoms which would place them at risk for anorexia.

The first time I remember encountering the gross fixation on bodies within the athletic world was in the place where all critical thought goes to die: the YouTube comments section. I frequently watched videos of Olympic gymnastics, and this time I was watching clips from the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.

Shawn Johnson and Nastia Liukin were the two frontrunners of the 2008 American women’s artistic gymnastics team. The two gymnasts were worldwide favorites to win on most apparatuses and in the all-around category.

Comments on clips of these two gymnasts competing at the Games are riddled with phenotypic and anatomical observations of Johnson and Liukin. Often, the two are directly compared to each other, and keyboard judges posited that Liukin’s domination on bars was due in large part to the natural grace of her lean body, as opposed to Johnson’s stout frame, which some commenters lamented would “thunk” down the balance beam. Though there were several comments praising the gymnasts’ skillfulness and athletic prowess, there were just as many detractive comments about how the athletes looked, most concerning the aesthetics of their bodies.

Following the 2008 Olympics, Johnson battled an eating disorder – unsurprisingly due in part to widespread media attention focused on her body. She spoke later in an interview about an unspoken mentality in gymnastics that associated better athletic performance with weight.

“Society, stereotypes [were to blame for how I felt about my body]. I don’t think it was one person. It was a simple mentality in our sport that the lighter you are, the better you look and the better you do,” Johnson said.

Simone Biles – the all-around gold medalist in women’s artistic gymnastics in the 2016 Olympics and the most decorated American gymnast – has been the target of many cruel remarks regarding her physical appearance, despite the attention that should be given to the sheer magnificence of her gymnastics.

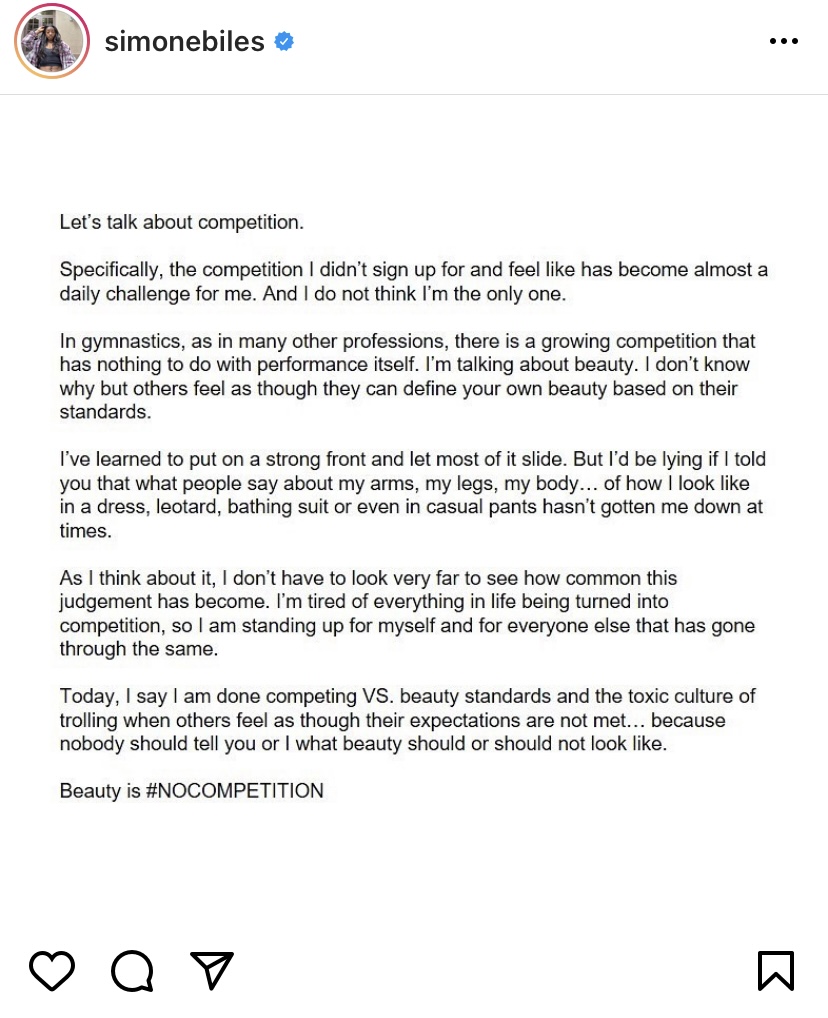

In February of this year, Biles made an Instagram post detailing her frustration with harmful beauty expectations as they’ve been applied to her in her athletic career.

With resolve, Biles ended the post by saying, “Nobody should tell you or I what beauty should or shouldn’t look like.”

And yet, the media, commentators and sports fans do, and they have been for a while.

Though she is now predominantly associated with her scandal, Tonya Harding first made headlines in the early 90s by being the first American woman in figure skating to land a triple axel in competition. Accompanying those headlines, however, were nasty references to Harding’s “thunder thighs” in addition to criticisms of her outfit and hairstyle.

Yet, was it not Harding’s “thunder thighs” that propelled her high enough to land the triple axel?

The same goes for Johnson and Biles: Is it not the same bodies the media have criticized that allow Biles to flip 10 feet into the air or Johnson to confidently land her inconceivably difficult beam series?

While being praised for groundbreaking athletic feats, women in sports are constantly being denigrated for the same finely trained body parts that enable them.

In sports like figure skating and gymnastics, where the athletes are literally being given point values for how their bodies look – the point of their toes, the angle of their bodies in the air, the confidence of their landing – the audience often feels justified in making critical observations about athletes’ appearances. Observers impose a homogenized standard of beauty onto athletes, yet fail to realize that it is the very physical diversity of athletes itself that make sports so exciting to watch.

Furthermore, it’s simply silly and degrading to expect these women to look like fashion models. They’ve trained, often for a decade or more, to be in peak physical form and have become the best of the best in their sport. Their bodies are physical manifestations of dedication, grit and perseverance.

Even beyond elite sports, the danger is still apparent. All athletes – men and women, from recreational sports all the way up to the Olympics – hear a certain set of narratives regarding their bodies. Athletes are told they must be trim and lean. Excess fat is something to be burned off through a stricter diet or harder training. That’s why the rate of eating disorders among athletes is so high.

It’s evident we have to change the narrative. Training for and competing in your sport should have nothing to do with mainstream ideals about physical aesthetics.

I can recall my teammates frequently making negative comments about their own bodies, too, though I never thought too much about that because I was too consumed by my issues with my own.

Sometime after my experiment in weight loss, one of my teammates lamented the few pounds she must have gained while examining her stomach in that same mirror-lined wall. This was a frequent occurrence among the post-pubescent girls in my team.

This time, my coach overheard, clearly perturbed, and she said something that still sticks with me when I get upset over gaining weight.

“You are beautiful,” my coach said, “because of two things: You are healthy, and you are strong.”

And that’s all that should matter.