Home to almost 500,000 people, Kansas City is a rental metropolis. Yet – despite over 200,000 people occupying rental units – rising costs, limited mobility within the city center and an increasingly unstable job market contribute to a turn-over housing culture in which eviction has become a profitable business model for landlords.

Eviction is a legal process in which landlords expel tenants from their properties for failing to pay the rent or violating other terms of the rental contract. Before court consideration, the dispute may be settled between the landlord and tenant. If tried in court and a judge rules the tenant guilty and must leave the property, Missouri state law dictates the eviction will remain on the tenant’s record for the next seven years.

Legally, eviction notices are duly sent and tenants are provided adequate notice ahead of courtroom summons.

Gloria Fisher, executive director of Westside Housing – a community development corporation in Kansas City – explained that tenants of Westside apartments are given about 100 days notice before being summoned to court.

“If someone doesn’t pay rent we send [them] a notice at the end of the month. […] If [we] haven’t heard from the tenant two months in a row [we] start the rent and possession process,” said Fisher.

For landlords, the process of each eviction can be costly.

“I’m out anywhere from 3-5 months rent plus the legal fees,” said Fisher. “We want the renters to pay on time because eviction is a high cost for us.”

Westside provides income assisted housing units priced between $330 to $825 per month, significantly lower than the average cost of market value housing in Kansas City. For each eviction, Westside risks losing up to $6,000 in lost rent and legal fees.

“At Westside, we’re a small not for profit and basically we need people to pay their rent every month,” said Fisher. “We’re close to downtown and not near as expensive as the market rate apartments […] people live in our buildings and they pay, that’s how we keep things maintained.”

Tenants do not always pay their rent on time. There are countless reasons for why a person cannot make their rent payments, including the loss of a job, death of a family member or unforeseen personal expense.

Cory Reames, resource development coordinator for Westside, explained that regardless of the circumstances, if a tenant cannot make their rent payment on time – or come to an alternative agreement with their landlord – they will suffer long-lasting consequences.

“It’s not criminal to be evicted, however it is criminal to not pay for what you’re responsible for paying in a contract,” said Reames. “It’s likely that your eviction status will follow you and renters will be less likely to grant you a lease […] one eviction could lead to months or years of homelessness.”

Image courtesy of Sofia Arthurs-Schoppe

Both tenants and landlords capitalize on this situation, as Fisher explains.

“There are people who plan to get evicted because it gets them three or four months of free rent,” said Fisher. “There are landlords who, as soon as you move in, they begin the eviction process.”

Lori Wetmore, professor of chemistry at William Jewell College and member of the KC Equity Network, attested to the profitability of this business model.

“[It’s] like a revolving door, landlords seek to profit off tenants and get them evicted quickly, it’s a profitable business model,” said Wetmore.

By renting out poorly maintained properties at cheap costs and evicting residents who withhold rent in protest, such landlords profit off legally obtained payouts in local and state courts.

“The problem is that the tenant can withhold rent but then the landlord will take them to court and how will the tenant fight them? How are they supposed to pay for a lawyer or even get to court when they need to be at work?” said Wetmore.

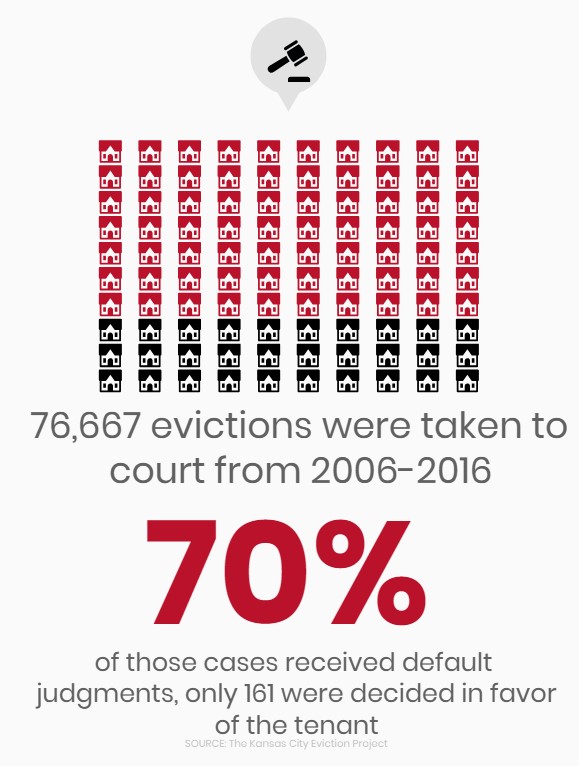

Michael Duffy, managing attorney for Legal Aid of Western Missouri, an organization providing free civil legal assistance to low-income families and individuals, has observed the courts generally rule in favor of landlords.

“Most lawyers who appear in landlord/tenant courts on behalf of the tenant say that it’s unfair and I would agree with that,” said Michael. “There is usually very little time to prepare cases… and it is pretty typical for landlord/tenant trials to only last about 60 seconds.”

Courtesy of Sofia Arthurs-Schoppe

But the problem goes beyond preferential treatment in the courtroom. Some statutes in Missouri state law subject tenants to the mercy of their landlords, regardless of the outcome of the trial.

For example, regardless of the legal outcome of an eviction case, tenants are entitled to a return of their security deposit so long as they pay back the rent they owe. However the law states that before returning deposits, landlords may remove the cost of maintenance and repairs to the residence – meaning that tenants only receive the deposit less whatever the landlord chooses to charge for the property.

Aware of these issues, Wetmore has been active in lobbying the state government to pass the “Healthy Homes” initiative (Question 1), which was approved by voters Aug. 2018.

While the city health department usually inspects rental homes and apartments for potential health hazards, under Healthy Homes inspectors will respond to tenant complaints and will conduct unannounced visits to properties they suspect to be hazardous. The initiative will be funded by a $20 per unit annual fee charged to landlords due when they register their properties with the city.

“People can now anonymously or publically lodge a complaint about issues in their apartment and inspectors will come and then hold the landlords accountable,” said Wetmore. “[The initiative] gives some power back to the tenant.”

Dan Edwards, managing principal at Digital Builders LLC and co-founder of Movement KC – a vocal anti-gentrification and pro-affordable housing advocacy group – believes the solution to Kansas City’s housing epidemic lies on the underdeveloped east side of Troost Ave.

“We’re housing all the poor people to one side of the city and the wealthier people on the other side,” said Edwards. “I get pissed off when there’s the capacity to do more and people choose to profit off a [perceived] incapacity at the expense of others.”

Edwards advocates the construction of more market value houses on the east side of Troost to facilitate the creation of a mixed-income neighborhood in Kansas City.

The construction of such neighborhoods has been a controversial subject in Kansas City – some attribute the controversy to a cultural misconception.

“That’s how it’s understood to be, that low income is less secure or less neighborly,” said Reames.

While it has been shown that the presence of affordable housing units raise the value of nearby properties and increase diversity, miseducation creates a stigma which prevents more of these units from being built in Kansas City.

“You hear the same kind of thing: disinvestment in the urban core, schools that are broken, sidewalks that are broken,” said Fisher. “We all want affordable housing to exist, but the suburbs don’t want [an affordable housing] unit to go up.”

The issues in Kansas City are not unique. In fact, what we see here is part of a larger national housing crisis, one which affects all aspects of civilians’ lives – from safety to education, healthcare to mobility.

This crisis is undercut by the Trump administration slashing the affordable housing budget. These cuts result in a decrease in funding for organizations like Westside – which is funded by the congressionally operated Neighbor Works program.

Photo courtesy of mcdanielandscibal.com.