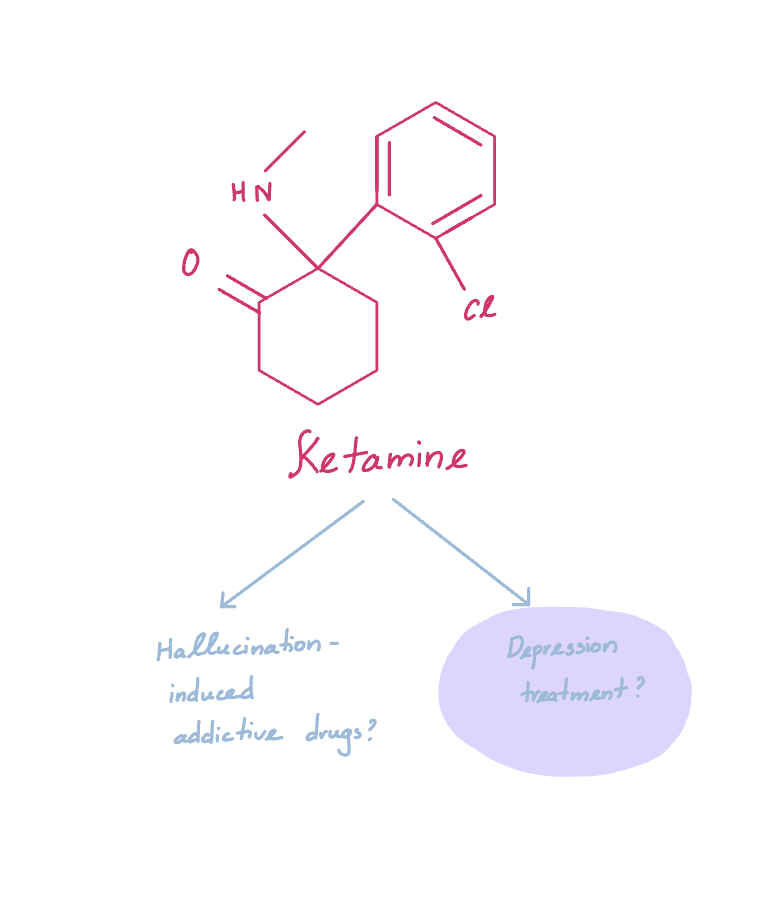

Ketamine is a promising chemical for depression research but should not be generalized as a first-line antidepressant.

Ketamine has been used to induce loss of consciousness for general anesthesia for decades. Recently, this medicine has been used as a second-line treatment in clinical trials and research to treat depression, which has sparked controversy. It is not hard to find news about addiction and misuse, or even death when you search for ketamine. Moreover, this drug is not approved by the FDA to treat depression. Despite its bad reputation, ketamine is a promising medication for depression and an impactful chemical for psychological disorder research.

Let’s first explore the reasons why ketamine can be a good alternative for standard treatment when those common medications do not help alleviate depression. The current antidepressants act to increase the level of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine neurotransmitters in the brain to make patients feel happier. As a new researcher myself, I consider this method ineffective. By enhancing the happy mood to treat depressed patients, researchers and doctors assume that depression is a mood disorder, and patients are simply unhappy. In reality, the causes of depression are much more complicated. A major one involves the alteration of synapses’ size and activity which then affects the connection between neurons. Therefore, in an attempt to treat depression, medicine should aim to fix the changes in how neurons communicate. Through many years of research on cell culture and rodent models, scientists found that ketamine enhances the activity at glutaminergic synapses and increases synaptic sizes, which are heavily reduced in depression. In short, ketamine reverses some of the known physiological alterations. Ketamine treatment has shown success in reducing symptoms of depression in many clinical trials. A patient is eligible if common antidepressants have proven ineffective. Patients are treated with low doses of ketamine along with cognitive behavior training under strict treatment plans with research physicians.

Despite the promising results, ketamine should not be approved for general depression treatment. Research on ketamine is limited. Scientists have focused on the effects on the damaged parts of the brain (cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, etc.), but they have not explored the consequences of long-term ketamine usage on the brain as a whole. Ketamine is also highly addictive, leading to a potential long-term struggle for patients who are already mentally ill. We should think of the success of ketamine treatment as the groundwork to develop new medications that target the same neurotransmitter (glutamate) but without the addictive effects and other unknown consequences on the brain. Hopefully, a new medicine might offer a better first-line treatment for depression compared to the current antidepressants on the market.