Feb. 22, 2017, KCUR reported on the Experts from the Diary of Judge A.H. Shelton, a work that was recently compiled and published by the Clay County Museum and Historical Society. Former Historical Society President Jana Jesse Becker assembled the book, omitting all of Shelton’s writings on race relations in mid-19th century America—excluding racial slurs and mention of slavery—in order to avoid controversy. Yet, as KCUR wrote, these omissions work to sanitize history and de facto glorify the South’s institutions in the Civil War.

“The excerpted diary serves revisionist historians who [can] use it to portray the Confederate cause as a battle for state’s rights rather than a defense of slavery,” the KCUR article highlighted.

The Confederate flags that adorn many porches today in mid and southern America underscore this perversion of the Civil War as a conflict that was strictly over state’s rights.

However, the NPR article conflates a supposed dismantling of a Civil War monument honoring Union soldiers at William Jewell College in the mid-1990s as a similar distortion of history.

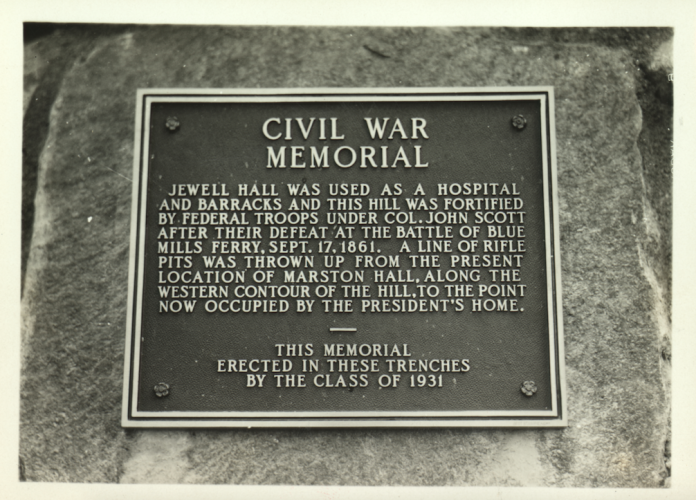

The monument to which the article refers was dedicated by the William Jewell Senior Class of 1931, commemorating fallen Union troops and their use of William Jewell’s campus during the War Between the States. This monument marked the first recognition of Union Army action in Clay County.

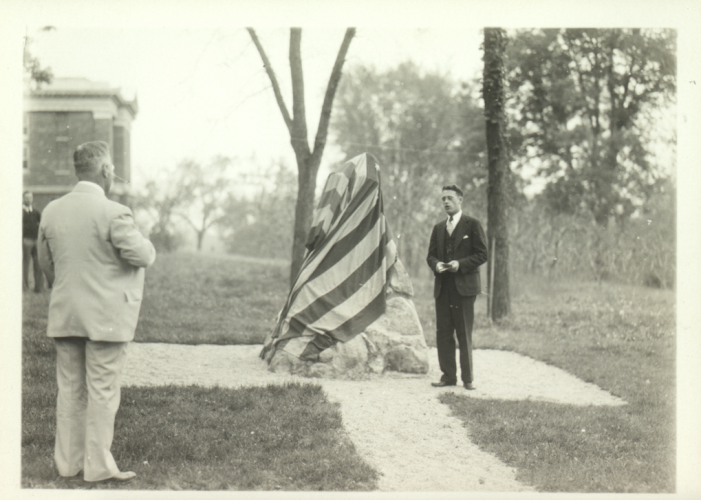

William Jewell Class President and senior Everette Webdell gave the dedicatory address for the Civil War memorial in 1931

In 1993, the stones of the Union monument, originally erected in the historic trenches down the hill at the base of Jewell Hall, were deconstructed, but its memory and significance did not disappear as the article alleged. The plaque delineating the Union’s influence at Jewell was simply moved to the grounds surrounding Grand River Chapel. Two other historic markers surround the chapel. These are tributes to the Union as well.

A picture of the plaque from the Civil War monument in 1931. Though the memorial was dismantled, the plaque still stands by Grand River Chapel today

The second marker showcases the history of the Civil War trenches which were built through Jewell’s campus. After losing the battle of Blue Mills Landing—also known as the Battle of Liberty—on Sept. 17, 1861, Union forces retreated to Jewell’s hill; they remained on the hill for weeks, transforming the first floor of Jewell Hall into stables, the second floor into barracks and the top floor into an infirmary for Union casualties. The next year, Union troops established their headquarters on Jewell hill and dug rifle pits from today’s president’s home to what is now Marston Hall and around Jewell Hall. These trenches were constructed in response to rumors of an impending Confederate invasion. The marker is placed where one of the three cannons stood ready to fight the encroaching rebels. However, the South never advanced to Jewell after the installation of the cannons so the trenches never saw war.

The third marker by Grand River confirms the mass grave site in Jewell’s midst. It memorializes the death of 17 Union soldiers who were killed in the Battle of Blue Mills Landing. The soldiers remained buried there until 1912 when their bodies were unearthed and reburied at Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.

William Jewell has long faced criticism that their construction projects that eliminate essential Civil War landmarks. A Kansas City Times article from Dec. 14, 1956 bemoaned that the advocates for maintaining the historic trenches had, like the Union forces in 1861, lost a battle.

“A preparation to erect a new student building caused the final assault,” the article reported. The Kansas City Times outlined other construction projects that masked the trenches, such as Carnegie Library built in 1906 and Marston Science Hall built in 1913. The new student union building covered the residual evidence of the trenches in this region of campus.

Debate again ensued when the flagstone patio was constructed in front of Grand River Chapel in Sept. 1993. Though the plaques commemorating the Union forces were placed nearby, the patio did destroy the most noticeable sections of the remaining trench line. This move was a blow to historians at the Civil War Roundtable of Western Missouri who declared the Civil War trenches at Jewell a “must see” site. “The trenches are not even outlined anymore…[William Jewell] made absolutely no attempt to preserve this. Everyone feels the college intentionally deceived us about what was going on,” said Sonny Wells, historian and President of the Civil War Roundtable.

Jewell has attempted to balance the tension between preserving its heritage and adapting for future students. According to Cara Dahlor, William Jewell’s Director of Communications, Jewell constantly makes an effort to safeguard and share its history.

“Any time we talk about William Jewell College, we’re proud to share our history,” said Dahlor.

Jewell Cardinal Blazers stop at Jewell Hall to disclose its historical significance to the Union effort on all Jewell tours. The college also partners with Historic Downtown Liberty to initiate local walking tours of Jewell’s Civil War history.

Transparency about its history and new projects that may jeopardize historically significant spots has been a priority of Jewell. “There are references all over our campus to our history,” said Dahlor.

Along with the markers near Grand River, the history of the college is sketched in the interior of the PLC; informative plaques decorate the exterior of Jewell Hall. As for the patio project, it was well-publicized. “We discussed plans for the landscaping of the chapel…An artist’s rendering for the plans was displayed. It was all discussed very openly,” said Rob Eisele, Jewell’s Director of Public Relations in 1993.

“It’s too bad they’re gone; they were such a part of our heritage,” said Wells, referencing the bulk of the trenches in front of Grand River. “You could reach out and touch them. But now you can only look at pictures.”

Though Jewell may struggle, in some historians’ eyes, to adequately defend all of its historical landmarks as it continues to expand its infrastructure, it attempts to openly and accurately tell its history and relationship with the Union.

I find the above article to be ambiguous as to the preservation of the Civil War trenches on campus.

At some point, the College apparently disregarded these important, silent reminders of what our forefathers

endured to build a better America. Do any of these trenches still remain? If so, are they protected from people walking upon them through signage?

Are the trenches explained to the public? If so,

is there an historical marker to commemorate them? These trenches are of national interest and importance. You are lucky that these historical landmarks are upon your campus, which causes additional collegiate notoriety. You folks are the trustees and fiduciaries of these trenches.

As we approach the 250th birthday of our republic next year, please give America the gift of historic preservation, as well as excellent student graduates. Please respond. Thank you.

the preservation of these landmarks. Kindly respond. Thank you