Western media has fabricated a genocide in Xinjiang to justify economic and political interventions aimed to undermine China’s incredible growth. Horrific stories of Party campaigns forcing “sterilizations, IUDs, and mandatory birth control” upon Uygur populations continue to surface in the west. Yet the evidence garnered by investigative journalism is slim.

The research upon which the horrific anti-China claims chiefly rely is Adrian Zenz’s study of birth rates in Xinjiang. Yet, a systematic review of the official documents Zenz cites in his study demonstrates repeated construal of evidence and deliberate fabrication of facts.

Beyond this, we must be attentive to Zenz himself, an evangelical fundamentalist Christian associated with the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. This is an organization dedicated to tarnishing the memory of communist achievements with fabricated data, barring communists from free speech, and obscuring the ideological legacy of communism through conflations with Nazism and simple equations to authoritarianism.

When Zenz, the German Christian evangelical, is not fighting a righteous fight against the repression of Uygur Muslims, he is busy explaining that Jewish people will burn in a fiery furnace during the end times. If we are attentive to the character that Zenz himself displays, it is clear that his concern is not really about the Uygur Muslim people – whose eschatological fates are the same as those of Jewish people. Zenz’s concern is Sinophobic and anticommunist.

Once you get through a swamp of articles all parroting the same narrative, the actual evidence to suggest a genocide in Xinjiang is thin. The evidence that no genocide is occurring, on the other hand, is compelling. There is, of course, the obvious fact that in spite of this supposed genocide the Uygur population, life expectancy and average income continue to rise. There is also the curious absence of a refugee crisis in the region, something which would seem almost certainly to follow from the level of ethnic violence and political repression western media has described. And if China wanted to repress Uygur culture, why would it write the Uygur language onto their currency?

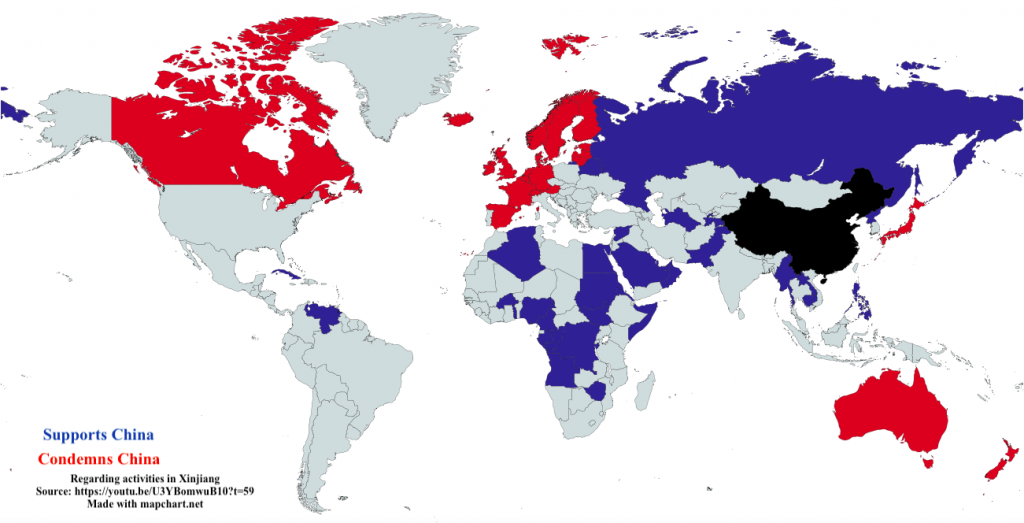

It is important to consider the demographics of those who support versus those who accuse China. Despite the Uygur people being a Muslim population, not a single Muslim-majority country joined a letter to the United Nations criticizing China’s activities in Xinjiang. On the other hand, 54 nations, most of which are Muslim-majority states, responded with their own letter to the UN in support of China.

Still, western countries engage in their anti-China campaign, most recently in the imposition of sanctions against cotton growers in Xinjiang accused of utilizing coerced labor from detained Uygur people, despite that the mechanization of cotton harvesting has increasingly made manual labor obsolete in Xinjiang’s cotton industry.

Western nations impose these sanctions despite stories from Uygur cotton workers in Xinjiang who describe a profound respect for distinct customs and culture, and reports from third party diplomats who observed the same sort of respect and community between multiple cultures. Likewise, interviews with Xinjiang residents demonstrate consistent denial of western accusations – some interviewees went so far as to couch the western media project within a larger imperialist scheme.

In fact, the most likely population to face economic harm from the western sanctions are the Uygur people in Xinjiang where cotton production is a staple of economic health. This seems to not be an accident. A video shot in 2018 recently surfaced of Lawrence Wilkerson, chief of staff for Colin Powell during his time as secretary of state, in which Wilkerson suggested that the best opportunity for the United States to destabilize China would be to exploit Uygur people in Xinjiang.

The western sanction policy aims to exploit the deep history of terrorism in Xinjiang by driving Uygur people to unrest through economic sanctions aimed to bar the Xinjiang cotton industry from reaching standards of modern industry. If the west can lock Xinjiang’s economy below modern development standards, unrest and terrorism will likely resurface in this region which has enjoyed security during the past four years of impressive economic improvement.

While the Minister Counsellor from the Maldives embassy in China remarks that the international community should take Xinjiang as an example for how to bring people out of a social problem, the official western narrative continues to be condemnation of forced labor, ethnic repression, and genocide in Xinjiang. This tension is palpable on the global stage, demonstrated by an endless array of infographic maps displaying polarization between the global northwest and global southeast.

Let me now suspend the aura of objectivity with which I have proceeded to this point. I wrote, in the form of a factual statement, that no genocide is occurring in Xinjiang. I have defended the factualness of this claim with a wealth of citations. Yet the diligent reader may have noticed that many of these citations lead to media sources operated or funded by the Chinese state.

I have, of course, been citing Chinese propaganda, and I have cited it as objective fact. Does this seem to be a problem? Perhaps. But before making a final judgment on that, we should briefly glance at any of the articles ordered as “News” in this periodical.

Practiced constantly in news media is the statement of claims as objective facts – this appeal to facts is the form of news as we understand it. The articles called “News” – and thus understood to be more objective than “Opinion” – proceed by stating claims as facts and citing other media sources which make the same claims. This is the precise form I was utilizing above, only with references to Chinese rather than western propaganda.

We should, of course, be skeptical of the power interests being served by Chinese state media. Yet to critique only Chinese media without also approaching western media with a skeptical mind is to be nearsighted and Sinophobic. Power is not pure simply because it is white – or more exactly, European-derived.

Of course, we in the west love to boast of our press freedom. Westerners assert their market-based media apparatus as superior to the state sanctioned media of China. Whereas in China any semblance of independent media is already constrained by the state stranglehold on information, in the west independent research into free and competing information is a staple of political life. But what does this really mean?

Overwhelmingly, any information we receive from the western media apparatus can be traced back to one of three sources – AP, AFP, or Reuters. As these major agencies disseminate their stories to associated media outlets, the narrative grows and obtains the likeness of an objective fact. All news in the west tends to be authored with reference to the narrative crafted by one of the three agencies which write our so-called free press. If the information did not come from one of these three agencies, it came from an otherwise market-interested organization. For example, one organization that leads the publication of anti-China information is ASPI, a think tank funded by corporations that profit from selling weapons to governments that fear China’s rise.

China and the west, then, are not really that different. Whereas in China news is authored along the ideological lines of only two or three state sanctioned agencies, in the west news is authored along the ideological lines of only two or three market privileged agencies. The difference, then, is the interest being served by the information. In China information is authored from a viewpoint of the political interests of the Party, in the west – and paradigmatically in the U.S. – information is authored from a viewpoint of the market interests of a major media agency or another profit seeking entity.

In both cases, this is a matter of propaganda, a problem of the way that the production of information is first concentrated in a few hands with definite power interests and only subsequently disseminated throughout a social body via myriad distinct outlets. In both east and west, propagandists succeed in crafting a dominant social narrative by first controlling the origin of information.

I have, to this point, used the word “propaganda” in a way popular to our culture. I have spoken of propaganda as any political text or presentation aimed to manipulate the beliefs of its audience. This has been useful for drawing out a structuring principle common to power-interested media apparatuses globally.

But this is not the whole story of propaganda. Propaganda need not occur only from the top down – the most powerful propaganda is that which reveals cracks in the official narrative, that is, the narrative crafted when information is first being authored by those two or three power-interested sources. There is a kind of propaganda that seeks to undermine the official propaganda, but this critical propaganda is not concentrated in the hands of a powerful few. This is the propaganda of the oppressed.

Critical propaganda must take a different form entirely than the official propaganda, because critical propaganda is aimed to destabilize rather than edify oppressive power relations. I borrow the following definition for the critical type of propaganda: a lengthy “examination of an issue or question in an all-around way, paying attention to the history as well as the motion and development of a contradiction.”

What I aim to be writing here is, of course, propaganda, only the propaganda I seek to create is critical and dialectical. There is a contradiction that can be demonstrated by the way dueling power apparatuses respond to claims of human rights violations. While the U.S. criticizes Chinese treatment of Uygur people, China criticizes U.S. treatment of black people or the humanitarian crisis at the border and its connection to U.S. imperialism, and in response, X criticizes Y’s treatment of Z people. The cycle continues.

There are two major propaganda forces that publish irreconcilable stories every day. In response to the criticisms of the other, the forces each assert more strongly their own dominating narrative. We cannot trust that either of these forces are giving us facts, only narrations vested in definite power interests. Yet in this contradiction internal to the structure of the official ideologies is revealed a truth about state power itself: oppression composes state power. In truth, atrocious behaviors occur everywhere, and every sovereign state would be best to conduct its own affairs with a mind to abolishing systems of oppression which have accrued throughout its own history.

We do not here face the problem of “fake news” which fascinates so many people who hold Zenz-esque ideologies. This is not a simple matter of right or wrong – it is a problem with power and it is a historical problem. To parse out facts, we must critically engage the media we can access with special attention to the power interests being served by whatever stories we encounter. The facts will always be on the side of the oppressed.

Plenty of anecdotes have been published of Uygur people detailing the horrible repression they faced. We should not be dismissive of these as Chinese state media overwhelmingly is. We should be attentive to the horrible accounts to which we have access. We should be wary of the way some discursive relations practiced in Chinese state media might dehumanize Uygur people. One anecdotal account of anti-Uygur violence analyzes that “‘terror’ now frames Uyghurs as ‘subhuman,’ much like the framings of native populations as ‘savages’ during the European and North American wars of conquest and accumulation.”

What is most striking to me about so many of the personal accounts I read is how remarkably similar they sound to anecdotal accounts of antiblack state violence in American inner cities. For the same reasons why we should disapprove of western media’s fascination with black death, we should be careful not to instrumentalize Uygur narratives in harmful ways, which can be easy for a media apparatus whose facts depend more upon the official narrative than upon thorough investigation.

No media apparatus will give us the answer, only the historical movement of the oppressed against their oppressors will make manifest the truth. If the Uygur people are to be liberated, it certainly will not be by the work of a U.S. government that keeps its black population in chains.

The Uygur case is an important one to consider from the position of a westerner, and it is most important when considering a case such as this that one does not jump too hastily to conclusions. We should be attentive to the geopolitical interests of the west in containing the cotton industry in Xinjiang. We should recognize the history of data fabrication in the justification of imperialism – it is not difficult not to remember Iraqi WMD production facilities in the drone images of Chinese concentration camps. We should be skeptical that the west is so worried for the plight of Muslim people in China but not for the plight of Muslim people under U.S. military drones.

This is not to say that we should simply accept Chinese media. We should be skeptical of the power interests underlying all production of information. Nonetheless, it is interesting to put into tension the official ideological lines of dueling media apparatuses.

While in the U.S., topics like universal housing, the right to food and whether black lives matter are up for debate within the official ideology – and indeed this is touted as freedom of expression – in China the official ideology expresses a strong commitment to eradicating poverty, providing universal housing, education, sustenance and healthcare, and a commitment that these policies should apply to every ethnic group living within the Chinese state.

The official Chinese ideology is dangerous to the official western ideologies. It is particularly dangerous to the ideology of American capitalism. Whereas Chinese state media expresses the commitment of the Chinese Communist Party to securing a guarantee to life for all people in China, we in the United States live in a society profoundly textured by the absence of any guarantee of our means to life. We are guaranteed nothing if we do not enter the wage-market, and even then, we are guaranteed nothing.

Fascination with Chinese violence performs an ideological mystification. The ideological commitment of the Chinese Communist Party to universal housing, sustenance, education and healthcare is marred in western capitalist ideologies. “Communism” in a western capitalist ideology is a word which denotes – far from anything to do with the writings of Marx, Lenin and Mao – only authoritarian violence.

It is far too easy when speculating about Chinese concentration camps to forget, for example, the plight of detainees in the St. Louis concentration camps. The fascination with humanitarian abuses by the Chinese government may sinisterly function to position the U.S. on a moral high ground at which it remains above coming to terms with the fact that, while the Chinese government expresses commitment to providing all people in China with their means to life, the U.S. government itself embodies the genocidal legacy of this plantation society predicated in black death.

This is not a defense of the Chinese state. We should, of course, remain concerned that the Chinese government has not denied that the counter-terrorism activities in Xinjiang occur at “re-education centers.” We should worry about the ease of using “anti-terrorism” to justify state terror. We should take great care not to dismiss the horrifying anecdotal evidence from Uygur people who have fled China. We should wonder why Chinese state media is so brief in its investigation of the destruction of mosques in Xinjiang.

I intend instead that this be taken as a strong defense of our critical duty to accept no media narrative without lengthy analysis of the contradictions of power being played out in the move to any particular narrativization.

The move by western media to label activities in Xinjiang as genocidal is a distinct political tool. U.S. charges of genocide weaponize the deep impulse of liberal humanitarianism which has historically operated to justify managerial interventionism and to obfuscate the ongoing legacy of genocide on U.S. reservations, in U.S. prisons and by U.S. foreign policy. The China problem highlights what is at stake in the way we talk about other nations and the way we go about questioning the treatment of people by other governments.

China is seen as a problem, or a threat. China is on a rise, and western ideologues have been scrambling in recent years attempting to devise the best containment strategy. The problem is that, in our grammar, China – the word itself – is a place-name to denote what is antithetical to the western values of freedom, individuality and democracy. When we in the west talk about China, we tend not to be talking so much about the society composed of really existing people, but only about the idea of unfreedom itself. This sinisterly functions to associate the Party’s expressed commitment to universal housing, healthcare, sustenance and education itself with a commitment to unfreedom. Thus, we in the west, against the knowledge of unfree China, can enjoy our freedom to sacrifice our lives to market exploitation.

The way western media – particularly dominant English-speaking media – talks about Chinese officials mimics too nearly the way it talks about thugs, gangs and criminals in the justification of a war on blackness. We should be skeptical of power-interests always, and we should be attentive to the way that our speech about China’s treatment of Uygur people has political implications that may not immediately be apparent.

In the same sort of way that “gang warfare” justified antiblack law and order policies domestically, “genocide” seems to be in the process of justifying anti-China hegemonic policies abroad. And our discursive treatment of Uygur people as a population to save operates to obfuscate the antiblack and anti-Islamic violence which seems to be the defining characteristic of current U.S. hegemony.

The problem with official propaganda is that the narratives always proceed from the interests of a few, then present themselves as interests universal to all people living within the social body. These distinct interests, represented as the interests of all, are in fact the interests of a distinct system of power, advanced by those who embody the role of an oppressor.

This is why there is an urgent and constant need for critical propaganda, for a mode of propaganda that seeks to upset the official narratives, and which expresses clearly its interests. I here have attempted to write critical propaganda reflective of the interests of all oppressed people. This article is vested in an interest to develop the power and understanding of oppressed people in casting off the chains of oppression and commonly sharing power without a hegemon.

For all on earth living under conditions of oppression: Dare to struggle, dare to win.

All power to the people.

Note from the author, (4/16/21):

It has occurred to me, in between the time of drafting this and the time of its publication, that my intent in comparison of anti-Uygur and antiblack violence may be obscure. Let me make clear that this is NOT an analogy. Afropessimism teaches us that there are no analogues for antiblackness; further, that any attempt to analogize antiblackness and dehumanization (e.g. anti-Uygur repression) is false and obscures our understanding of antiblackness. The logical form of dehumanization requires the possibility of rejoinder with humanness, i.e. a point of entry into humanist discourse; it is precisely this that Afropessimism teaches us is always already foreclosed to blackness insofar as the concept of the human is only able to mobilize its technology against that which it implicitly renders absolutely other, absolutely non-human (although even this register may be misleading about the amount of “being” blackness is allowed to claim in humanist logics), i.e. black.

While I do not intend to analogize the dehumanization of Uygur people with antiblackness (which is NOT a form of dehumanization but is the very condition of possibility for de-HUMAN-ization, as the model for non-humanness), I nonetheless think that important dynamics of state repression can be commonly demonstrated in both cases, even if the logical form of violence remains irreconcilable.

The important thrust of my thesis here, informed by Afropessimism, is that western anti-China rhetoric is mobilized by the logic of antiblackness, even as the logical form of particularly anti-Chinese violence culminates as dehumanization of Uygur people (which is irreconcilable with the logical form of antiblackness). There is no separating our anti-China rhetoric from anti-Uygur dehumanization and, more fundamentally, antiblack violence.

Nice article glad to see that journalism isn’t totally dead but some people actually care about finding out the truth.