The Problem

Last year, Americans spent an average of eight hours and eleven minutes looking at a screen every day. That is a scary number. When we look around us, devices are everywhere. We spend, on average, one-third of each day and half the time we are awake in front of a screen of some kind.

Not all technology is bad, though; many beneficial uses of technology exist. We have all probably used spell-check software to remove embarrassing typos or artificial intelligence to do research for an assignment. As I’m writing this line, I have Microsoft Word open to write this article, Firefox open to research it and Taylor Swift’s “Suburban Legends” playing in my headphones. I use lots of technology.

And you probably do, too. Unless you are reading this article in the December 2023 print edition of the “Hilltop Monitor”, you are using a device of some kind—whether mobile phone, tablet, or laptop—to read this. Technology can serve humanity in all sorts of ways. We cannot deny that we are living in the Information Age.

But this relationship—technology serving humanity—is often reversed.

The Culprits

In an essay for New York Magazine, ominously titled “I Used to Be A Human Being,” Andrew Sullivan draws our attention to what seems a very simple statement. Mobile phones are, well, mobile. “At your desk at work, or at home on your laptop, you disappeared down a rabbit hole of links and resurfaced minutes (or hours) later to reencounter the world. But the smartphone then went and made the rabbit hole portable, inviting us to get lost in it anywhere, at any time, whatever else we might be doing.”

The emergence of the Information Age, especially social media, creates three critical problems.

1. Quantification of Social Standing

Social media causes the quantification of social standing. In other words, social standing now comes with numbers attached. Instagram, X (formerly known as Twitter) and Facebook all show (publicly!) how many people follow you and how many people interact with your posts. Snapchat shows you a Snapscore that increases every time you send someone a picture. YikYak has a leaderboard of people who use it, sorted by how many upvotes you receive.

These numbers on social media are a double-edged sword. Research from the University of Florida shows a significant negative impact on users’ mental health. People who look at “upward” connections—i.e., profiles that indicate the profile’s creator is “better off” than the viewer—came away with “deflated self-esteem.” In contrast, when people look at content indicating other users are “worse off”, they feel better about themselves. We trade short-term benefits for long-term detriment—while people do feel better in the short term, they do so at the expense of others.

2. Information Overload

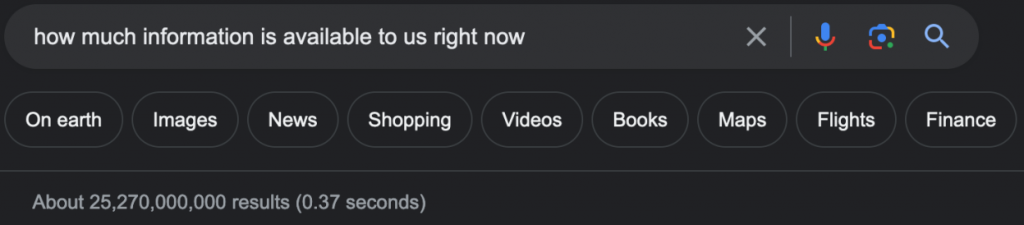

We suffer from information overload. We have access to worlds of knowledge at our fingertips: nearly two and a half quintillion bytes per day. If you type into Google the words, “how much information is available to us right now,” Google returns this:

This does not seem to be a problem per se. Sure, there is a lot of information to sort, but there is nothing wrong with the information existing. Processing that information, though, requires our attention. As such, humans have to triage; we discern what is important, focus on those bits and disregard the rest.

However, the internet puts that system into overdrive. “Viewing and producing blogs, videos, tweets and other units of information called memes have become so cheap and easy that the information marketplace is inundated,” write Thomas Hills and Filippo Menczer of Scientific American. We do not have the ability to effectively parse everything, so our biases take over.

This inability to fully process stimuli activates what I call our “lizard brain.” We are unable to determine fact from fiction or beneficial information from bologna. Critical thinking ceases and we are open to misinformation. We need only look back two years to understand the cost of such misinformation. A Brown University analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic estimates that 319,000 lives could have been saved with vaccinations. That is ten times the population of Liberty, Missouri!

3. Virtual Substitution

Social media, messaging apps and podcasts serve as a virtual substitution for human contact. This does not seem like it should be a problem, either. After all, research exists linking “[the] quantity of one’s virtual interaction partners… [and] better mental health at both the daily level and the weekly level.”

Virtual interactions are wonderful, especially when distance makes in-person interactions impractical or impossible. But if we lack meaningful physical contact (because we limit our interactions to being virtual), we do not benefit as much. Multiple studies indicate that in-person interactions are more fulfilling; Zoom fatigue is real!

We have to take time to talk to the people we care about. If distance makes doing so impossible, maybe give the person a phone or video call. It is so much better than texting, as we can hear a person’s voice or see their face in a call.

The Solution

So what can we do? Fortunately, the Internet has plenty of information on how to avoid the devastating effects of the Internet. (Ironic, I know.) A notable work in this field is Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism. In the latter half of his book, Newport provides solutions to escape the world of technology. I have used his recommendations to outline three easy recommendations and one difficult recommendation for busy college students.

The whole text of Digital Minimalism is worth a read; if you want to read it, it is available here for free from the Internet Archive. (Quick shoutout to the Internet Archive!)

1. Walk to Class Alone

In 1845, transcendentalist and author Henry David Thoreau expressed concern about an overly interconnected world. “We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas,” wrote Thoreau in Walden, “but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate.” Thoreau is not challenging the existence of the telegraph, far from it. If Maine and Texas had something important to say, then there would be justification for its construction. Thoreau is simply concerned with remaining intentional in communication.

Newport defines the phrase solitude deprivation as a “state in which you spend close to zero time alone with your own thoughts and free from input from other minds.” When this lack of solitude happens, we lose our sense of identity. I describe this phenomenon as “being afraid of my own thoughts,” however, we need time to be alone with our own thoughts.

“Ethan,” I hear you already saying, “I’m so busy with athletics or academics or extracurriculars or all three at once. How do I find time to do this?” You have more time than you think.

I often find myself (and see other people) with headphones on as soon as I walk out the door of my residence hall, keeping music or video content on for my entire walk to classes or to the Union. For those looking for an easy way to find time with their thoughts, consider walking to class alone. No headphones. Nothing playing. Just you, nature and your thoughts. You would be surprised what it does to you.

2. Stop Liking Things

Weird heading, I know. You might think I told you to not have hobbies, but that is not what I mean. Clicking ‘Like’ on something seems to be a standard way to say, “I like this! This is cool.” When Facebook introduced the ‘Like’ button in 2009, that is what it was supposed to be for. According to Newport, the ‘Like’ button was “introduced as a simpler way to indicate your general approval of a post, which would both save time and allow the comments to be reserved for more interesting notes.”

The quantification of social standing incentivizes people to constantly check their accounts, investigating to see if anyone else has ‘Liked’ their posts or story. But in terms of information conveyed, the ‘Like’ button conveys exactly one bit of information, the least amount of information possible to convey, according to information theory. “To say it’s like driving a Ferrari under the speed limit is an understatement,” writes Newport, “the better simile is towing a Ferrari behind a mule.” By conditioning our brains to accept ‘Likes’ instead of proper communication, we are selling our amazing communication capabilities short. We have limited the amount of fuel our communication can run on; we are literally receiving information one bit at a time.

3. Schedule Everything

Our lives are all defined by schedules. Every person at this College, whether student, staff or faculty, has a schedule to follow. For students, that could be a class schedule; for athletes, it could be a practice schedule. One easy way to limit your screen time is to schedule it.

Schedule time to check your social media, watch television or employ whatever form of screen enjoyment you like best. After that, put the screen away. Newport continues: “Without access to your standard screens, the best remaining option to fill this time will be quality activities.” This is a good blend of abstinence and enjoyment; while you do not have to give your media up completely, you are able to limit it in this way.

4. Detox

This solution is not for the faint of heart. If you attempt to detox, you will have to demonstrate significant self-restraint. When I first read Newport’s book as a senior in high school, I attempted this solution and failed to maintain the thirty days required of me.

Newport’s tough suggestion is to give it all up.

Take thirty days and eliminate all non-optional screens from your life. Newport considers a technology non-optional if “its temporary removal would harm or significantly disrupt the daily operation of your professional or personal life.”

Take Instagram, for example. In considering if Instagram is essential, one must ask themselves if temporary removal of Instagram would significantly disrupt their lives. In most cases, the answer is no (and no, finding out about events is not considered essential). However, if someone runs a business from Instagram (where, for example, they are posting handmade goodies to sell), then Instagram is an essential technology for them.

After the thirty-day detox, begin to introduce non-optional technologies back into your life. Doing so enables you to think critically about whether technology needs to be there or not.

If you are considering this, I seriously suggest reading the entirety of Newport’s book. He provides many more examples and much more research than I can include in this article.

Conclusions

At the beginning of this article, I noted that technology’s relationship with humanity was backward—that humanity served technology, and not the other way around. However, I sincerely believe we can undo this relationship by making our relationships both with technology and other humans intentional. By using our time wisely and using technology to our benefit, not to our detriment, we can save humanity from this servitude. The world is increasingly moving online; we must learn how to adapt.