I recently had a conversation with someone I had not talked to in a long while. I was feeling particularly unenthused with my life this day and was not especially in the mood for some mindless chatter. Something about the combination of the pandemic and the perception of the decay of the world as I know it has made me somewhat more antisocial.

Regardless, I waved aimlessly at this person from a couple feet away – maybe the pleasant spring breeze inspired some feelings other than misanthropy for once. But something about my wave communicated openness, and before I knew it, they had approached me and we were then sitting outside on a park bench, exchanging the usual how-do-you-do’s.

I’m not sure how we got on to this topic of conversation. I have to admit that I was only half paying attention to the actual dialogue. I think the person said something about being antisocial, and I said something to the effect that I was surely doing that this semester. Then, unprompted, this person said that I had changed quite a bit from the beginning of my freshman year to now.

Maybe I am a narcissist. Maybe we all are because when we are offered a little glimpse into how other people see us – I mean, really see us – we jump at the opportunity the way a cat jumps at the opportunity to eat unattended plastic bags. It’s weird and disgusting, and maybe slightly endearing and exasperating all the same.

Either way, what this person said to me was that I had become more me over my time at William Jewell College. I had to give kind of an enthused look at them. I could recognize, in a sense, that this was true. Objectively speaking, what they were telling me was undeniable – by ending my toxic, six year long relationship with my ex-boyfriend, by cutting off my abusive parents and by limiting contact with my extended family, I really had given myself enough space to become myself again.

The proof of this is how much I cringe when I see my old ID photo. I mean, who the hell is that? I was trying to embody a stupid ideal of femininity and selfhood that I couldn’t even unreflexively endorse. I look at myself in the mirror, and I can tell that I’m becoming more me. My ex-boyfriend would call me all kinds of slurs if he could see me now, with my short hair and my binder.

And it’s undeniable that I find myself thrilled at this new me. I like being, well, to put it frankly, a very gay academic who is a little too into moral psychology. I more than like it – I love it. I think of dating my ex now or contacting my homophobic mom and actively have to suppress gagging. I think I’ve grown up as a person, and I am ecstatic.

But it’s the ecstasy of a junkie. The ecstasy of St. Augustine stealing pears and sinning against God. To what extent is my joy at eating these pears, of enjoying these newfound experiences of so-called “true” selfhood just a rebellion against my parents? Against my abusive ex? And to what extent is it really me? And then, even if I’m really me when I’m being – to put it roughly – incredibly queer, it’s like I’m plagued by a demon.

I look in the mirror and feel pleasure at my reflection. Me! I enjoy the reflection that looks back, where once I never did. But at the same time, I hear my mother’s hissing voice shaming me. I hear my ex’s idiotic, unfalsifiable conspiracy theories ricocheting back and forth in my brain whenever I try to make any sort of claim about anything.

Always, the evil genius of my past comes to poison whatever first steps I’ve made into some semblance of happiness! I’m tossed and spilled in this internal contradiction that I’ve become. This roiling, broiling sea of teenage angst. Subjectively speaking, I’ve never been more miserable in my entire life, despite the fact that I’m no longer actively in the abusive situations that I used to be in. In being me, I’ve never felt less like me.

Funny the way life works. There’s a fancy philosophical term that you can use to describe what it is that I’m doing. Or maybe, what it is that is psychologically, causally occurring in me. Because I’m certainly not doing this, hence why I describe it as being possessed by a demon. Essentially, I’ve lived 18 years of my life surrounded by people who told me that who I was and what I valued was fundamentally wrong.

Not just wrong, actually. That what I valued was somehow disgusting, or inhumane, and that I should feel ashamed for loving who I loved, or wanting to look the way I wanted to look or wanting to even learn about the things I wanted to learn about. That all of my creative powers and my energies of self-direction were evil. So, it was not merely resentment for myself which I was taught, but ressentiment, if we want to get philosophical about it.

And when you’re in that kind of environment, where you’re not only told, but raised in a way that screams at you that you’re somehow evil or gross, it tends to deform your desires. That’s exactly what I have: deformed desires. I’ve internalized a narrative that was intentionally crafted to make me feel bad about myself and so all my desires toward myself are, well, deformed.

It’s fun to get philosophical in the abstract about it, I think. But I think it’s become less fun for me when it’s no longer abstract and I turn my philosophical glare inwards. It’s fun to do case studies and talk about people’s deformed desires when it’s not about you, but then when it is about you, and you do have to deal with feeling like you’re possessed by the devil, then you do all this fancy philosophical footwork and are left with the feeling that you’ve performed surgery on yourself.

And guess what? Now you have a very mangled-up patient that can now say “I have deformed desires,” but that in no way helps with the fact that the patient is mangled up and still has deformed desires. So here is my advice. Probably, my advice is very narrow advice. But I will draw from Levin, a character from “Anna Karenina,” to make some of my points. And maybe a bit from Nietzsche.

Like Levin, I believe in reason. I think that reason is the key to finding out the answer to the question “What is it to live rightly?” But I also think that, like Levin, I tend to be kind of an idiot in the way that I torture myself with reason and thinking about reason. Levin wants to use all these sorts of metaphysical theories about the nature of the worker and the relationship the essence of the worker has to the field in order to solve the question of what is to live rightly. Specifically, what it is to live rightly in relation to the Russian agrarian lifestyle.

But in digging around all these metaphysical theories, in trying to find some kind of way of putting in very clearly articulated premises the way to live well, in a way that is indefeasible, Levin mostly ends up torturing himself. In the entirety of “Anna Karenina,” he comes off as a generally very irritated character who wants to believe in truth, beauty and justice. He even has glimpses of such truth, beauty and justice, yet every time he tries to grasp it by using reason – by using treatises, by writing very complicated argumentation – he loses the nature of truth, beauty and justice which seemed so close to him only moments before.

I think I’ve become much the same as Levin. I want to put everything into very clearly defined boxes and premises and arguments, and I want everything to be rational. And then my life isn’t. And my desires aren’t. And I wake up in the morning, and I want to scream my head off. I feel shame at myself for feeling shame, and I feel shame at myself for being ashamed at myself – I can’t get anything in my psychic disposition to align with any measure of reason, I’m just screaming. I am in despair at the idea that if Plato’s polis was started, I would be the worst guardian because my parents treated me like garbage.

I can’t bear it. I can’t bear the idea of being an imperfect human being. I can’t bear the idea that my being imperfect is out of my control, that my being irrational is not something that I can fix immediately despite all my fancy philosophical footwork. Why don’t I cohere to reason instantly? Why was I treated this way? I hate the problem of moral luck. And similarly, Levin can’t understand why his life can’t be perfect either after he marries the love of his life. Isn’t this what he wanted?

Haven’t I also gotten everything I wanted? Why can’t I just be happy? Why aren’t things just falling into place? Why isn’t Reason the measure of my life? What is wrong with me? What is wrong with the world? Why aren’t things beautiful, true and just? Why are both Levin and I so irritated?

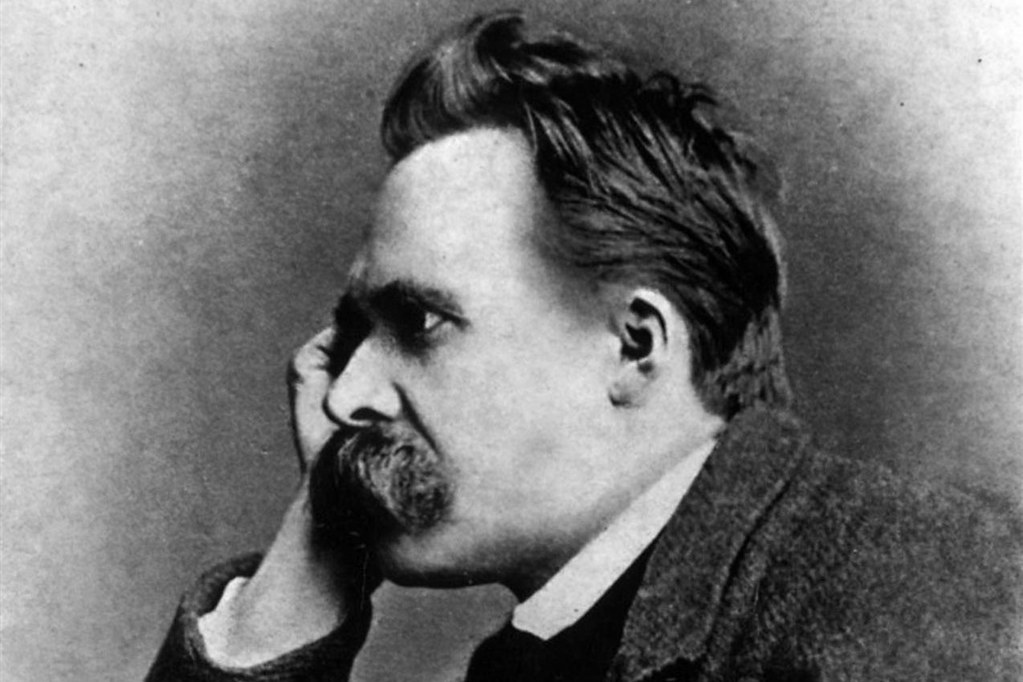

And the reason is that we are both fundamentally living like idiots. And if Nietzsche was still alive, I think he would probably hit me on the head – and Levin too. Probably, he would say something to the tune that I need to relax and read less Greek philosophy. I’ve become too Apollonian.

In other words, I’m overthinking it. I’m way, way, way overthinking things. I’m using reason not just as a tool to better my life, but as a tool to tear into myself for not being perfect due to things other people did to me. I’ve cut people who were abusive out of my life just to replace them with an even worse critic: the internal critic of objective reason. With me!

I am not at all taking seriously the fact that maybe I just know, emotionally, willfully, that I am living rightly. That when I look in the mirror and feel good, that it is good. That I don’t have to worry about stupid questions, about whether or not I’m just rebelling or paying attention to the voice in my head that’s my mom.

So what I’m telling you, dear reader, is not to use reason, or any of your other capacities, as a kind of doubt-raising tool against yourself. Don’t start your quest for autonomy and self-creation by looking for things that are wrong with you and start tearing yourself apart limb by limb looking for something that is metaphysically rotten within you. You’ll never find the source of your discomfort because it’s probably not even you. It was probably something that someone did to you or something that was not your fault.

Instead, take seriously that there’s something already within you worth keeping, something within you that already is good, and work with that. Human beings are not inherently evil. Most of us want to do good. Most of us are good. And I think most of us think there is something wrong with us and, in our desire to become good so badly, end up doing really bad things to ourselves or to others.

Perhaps we ought to relax just a little and remember that in the end, we tend to live rightly when we are not ripping ourselves to shreds. The task is self-creation, not self-destruction. Find who you are and then let yourself be that person. And remember that self-creation does not occur in a vacuum – other people exist to help you in that arena; to give you feedback and love.

I think this last point is pretty important too and one that is astonishingly easy to forget, especially in a pandemic hellscape. I tend to get stuck into a kind of doom cycle of thinking there’s something wrong with me, and then that’s reinforced because I get some kind of interpersonal interaction wrong and that leads me to flee from society. And fleeing from society is so easy now with quarantine happening, but it’s so bad for me because then I get even more stuck in my doom cycle of there-is-something-metaphysically-rotten with me.

I recently got this sense of sucking at interpersonal relations and did that thing where I disappear from the face of the earth in order to feel less humiliated. But this time, I ran back in despair to my old high school friend, Marissa. And while Nietzsche may be dead and cannot come hit me on the head with a book, Marissa is still a pretty good substitute and can philosophize pretty well with the hammer, despite being a computer science major.

I was crying to Marissa on the phone at being an abject failure at interpersonal relations. She was trying to comfort me. I’m usually impossible to comfort when I get in these sorts of doom spirals of feeling like I can’t get the measure of Reason. She asked me, “What do you think is wrong?” Here I felt a sense of relief because I thought that I could articulate, using my fancy philosophical footwork, what the problem was.

I began with my first premise: the problem of what I believe was my metaphysical rot, instantiated by years of poor habituation, which resulted in deformed desires. And how that ultimately culminated in my every external manifestation being also rotten.

It cracks me up to type this now, but I’ll never forget when Marissa interrupted me mid-rant to say: “Meta-what? What the hell are you saying to me? Plato’s “Republic”? Habituation? Are you literally trying to say that you think something is wrong with you and then that everything you do is wrong as a result? You’re so stupid! Shut up. You are literally fine and are just having a panic attack.”

If that isn’t philosophizing with a hammer back at me, I don’t know what that is. So dear reader, apart from advising you to not use reason or any other capacity to tear into yourself, I also recognize how difficult it is, for those of us who have a tendency to tear into ourselves, to actually remember that advice. I tend to forget it in five minutes. You should remember that you also have friends. And maybe some of your friends are hopefully infused with a more Nietzsche-like spirit and will cut right through your doom spiraling. Cling to those friends and help each other in your self-creation projects. We are, after all, social animals.