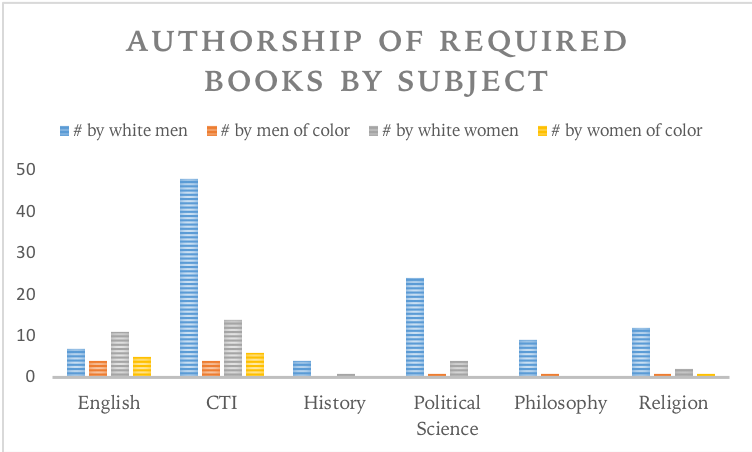

Of the 69 required books from Critical Thought and Inquiry (CTI) classes offered at William Jewell College this semester, 47 of their authors are white men, five are men of color, 14 are white women and six are women of color. One text, the Bhagavad-Gita, is of unknown authorship. 131 total books are listed as “required” on the syllabi this semester for classes in the English, History, Political Science, Philosophy (information from last semester, as no syllabi were available on Jewell Central) and Religion departments, including Oxbridge Institutions and Policy, Oxbridge Literature and Theory, Oxbridge History and Oxbridge History of Ideas. Of the 131 total “required” texts, 87 texts, or 66 percent, are written by white men. Specifically, in the History (including Oxbridge) Department, from information available on Jewell Central, there were zero required texts by people of color, while the philosophy and political science departments required only one each.

Courtesy of Christina Kirk

In looking at these numbers, it is important to realize that they are the product of only the syllabi available on Jewell Central. Additionally, research included only the texts listed as “required” for the course, not taking into account supplementary readings posted to Moodle or elsewhere, as those were listed in full only on some syllabi. Furthermore, the research does not account for how the texts are used. The fact of their use in the curriculum does not necessarily signal full or partial agreement by the faculty who assign them.

Although, according to the Pew Research Center by 2055 there will be no ethnic majority in the United States, books by white writers make up significantly more than half of the required texts in Jewell curriculum. Women, despite making up more than half of the world’s population, and more than half of the population at Jewell, are also underrepresented in the curriculum. In thinking about this issue more broadly, it is first helpful to understand the process both curriculum and syllabi undergo before being presented to students.

According to College Provost Dr. Anne Dema, Jewell operates under a system known in the academic world as “shared governance,” in which the faculty govern the curriculum almost entirely.

“Administratively we’re organized by academic departments and within an academic department it’s the department chairperson who then has the responsibility for ensuring that the curriculum is offered, as well as the quality of the faculty and what they’re doing,” Dema said. “Also then when it comes to proposing new courses all of that comes to approval through the department chair.”

Despite the great liberty faculty may exercise over the curriculum, the college does have certain requirements for syllabi, but these requirements involve mainly course management, not necessarily anything content related. The syllabi for each department are reviewed rigorously by their respective department and, according to Dr. Debbie Chasteen, professor of Communication and Chair of the Curriculum Education Policy Committee, are expected to be posted to Jewell Central at the beginning of each semester. According to information from the faculty handbook provided by Chasteen, “all courses should have a clear and accessible syllabus provided for each student. While the College does not provide a template for the syllabus, each syllabus should include the common elements listed in section 4.7. In online course syllabi, Faculty should include clear policies on what constitutes adequate participation in their course.”

These common elements include nature of the course content, requirements of the course, method of evaluation and class withdrawal policy.

Dema states that although her office does not control the specificities of curriculum, she does as much as she can to support faculty with resources for the curriculum they are offering.

With the college’s focus on Diversity and Inclusion this year, Dema says that conversations about diversifying curriculum are ongoing.

“The last conversation when it came the sort of texts and audit of that really was conducted as a part of the core faculty’s conversation about including diversity and inclusion,” Dema said. “So, that’s really where that conversation has taken place. I’m not aware that they have any particular requirements at this point. I know that they have talked about it.”

While there are not currently requirements about use of diverse texts in Jewell curriculum, there are two main curricular initiatives started this year focused on Diversity and Inclusion, the Diversity designated courses (DU and DG) and the CTI 150 course, required for all first-year and transfer students.

Dr. Gary Armstrong, professor of political science and Associate Dean of the Core Curriculum explains that the diversity designated courses are more about conversations and outcomes than specific reading material.

“Those are more about outcomes and the kinds of conversations, and not necessarily about the texts that are assigned”, said Armstrong, “In all of those classes, faculty may be assigning texts that they disagree with, that they want to have fun with and argue about. The heart of the Diversity and Inclusion work was our institution needs to be better about helping students grapple with hard questions about encountering the lived perspectives of others and then dealing with questions about power and justice in society. All over those courses, they could figure out what kind of questions, topics and assigned texts they want to use,” Armstrong said.

In CTI 284DU offered Spring of 2018, School and Society, the one required text is by John Rury, a white man. In CTI 238DU, Religion in the Modern Age, out of the three required texts, two are authored by white men and one is authored by a black man.

Aside from the diversity designated courses, for which there are certain requirements regarding “outcomes,” Armstrong explains that faculty have almost total control over their own classes.

“As a rule, we want faculty to have as much independence and autonomy to create the best course possible, so the faculty—sometimes it’s in faculty groups such as CTI 100, not so much in CTI 150—as a rule it’s very broad with very little oversight,” Armstrong said.

With this great autonomy, however, comes constant review of curriculum. Dr. Ken Alpern, professor of philosophy and Oxbridge Senior Tutor, told the Monitor that the tutors and the Oxbridge major coordinators are in constant review, conducting program wide reviews each year, but addressing other matters on a day-to-day basis.

Dr. Elizabeth Sperry, professor and chair of philosophy, as well as Dr. Mark Walters, professor and chair of English, both state that their departments regularly review the curriculum. Sperry states that they review texts on a syllabi each time the course is offered,

“If scholarship and/or student needs have changed, the course content and required readings change,” Sperry said. “Philosophy, like other disciplines, is dynamic and self-transforming. Since I first came to Jewell, feminist philosophy, which had been marginalized within the discipline, has become more mainstream. Philosophy of race has also become more mainstream. Accordingly, offering those courses is important both for reasons of social justice and to educate students in the discipline.”

Walters calls the oversight of the English department curriculum “always collaborative.”

“The curriculum and the courses within it were developed over a number of years by the members of the department according to the highest expectations of the discipline and the mission and identity of the college as a liberal arts institution focused on the development of critical thinking skills and cultural awareness,” said Walters. “The requirements for any course are determined by its level, its general subject matter, and the Program’s specific goals and outcomes.”

When asked about the majority of texts being written by white men, Armstrong pointed to a possible “lag” effect in certain subjects, which, still dominated by white men, means there are not very many texts by other demographics. He also noted that, the fact of a text being assigned does not signal agreement by a professor.

“[A professor] could be assigning texts from white males that they want to whack the heck out of,” Armstrong said. “I’m not sure that it reflects the hegemonic centrality of white male discourse.”

That being said, texts reaching canonical status in academic disciplines requires their use. So, to combat this lag effect, texts by a diverse group of people, which might not be considered canonical now, should be used. With increasing use, texts can gain increasing stature and relevance in the field, entering them into the canon.

Armstrong and others acknowledge the importance of diversity at Jewell and the necessity of many views in a curriculum.

“I think we want students to encounter a real sophisticated pluralism of views,” said Armstrong. “If students don’t think we are accomplishing that by what we are asking students to read and think about then we need to hear that and rethink what we are doing.”

Walters echoed Armstrong, noting the college’s liberal arts designation.

“We are a liberal arts college,” said Walters. “I take that in the most literal sense of freeing one—from narrowing habits, beliefs, customs and perceptions—through the enlargement of one’s understanding and intellectual abilities, best realized through interdisciplinary work.”

While many at Jewell have acknowledged the need for increased diversity, and certain initiatives like CTI 150 and the diversity designated courses are necessary steps in the right direction, there still exists the data on required curricular texts.

One possible solution is implementing stricter requirements about diversity, which has certain implications. First, it does not mean that canonical texts need to be discarded, or even that they should be discarded. There is plenty of room for canonical texts—as long as they are not used blindly—and new, more diverse texts. Second, imposing a set of required texts within curriculum, though technically a limit on the autonomy of educators, would foster greater creativity in educators. Certain requirements, by forcing educators to look outside the accepted canon, would aid educators in broadening their own knowledge of their subject.

“Education has a central role to play in the work of social justice,” Sperry said. “Academics should prepare students to engage fairly and complexly with the world. The world is, quite obviously, populated by many people who are not white, not male, not straight, not materially well-off, not able-bodied, not Christian and not cisgender. We must help students to understand the perspectives and problems of those not like themselves. We must also help students to understand how they have been shaped by social expectations so they can decide for themselves if they wish to accept or reject that shaping.”