In a constantly changing economy, William Jewell College has a distinct approach to the management of its endowment fund – one that that has been put to the test in recent years but has alleviated large amounts of debt for the College and enabled increased future financial flexibility.

Jewell, much like other higher education institutions throughout the United States, stores the majority of its financial resources in an endowment fund. This fund holds its principal in perpetuity, meaning it is maintained at a similar value over an extended period of time with no fixed maturity date.

Endowment funds are invested into funds and ventures that institutions believe will be successful and generate income. Over 90 percent of these funds remain invested and untouched throughout the academic year, while the vast majority of colleges and universities in the U.S. spend between 4 and 5 percent of their endowment annually.

Straying from the pack, Jewell chose to increase their endowment draw for several years to support the College’s operations and reduce debt. Since the early 2000s the College has made annual endowment draws as high as 11 percent in fiscal year 2008 and averaging at a rate of 8 percent between 2007 and 2017.

According to Brian Clemons, vice president for Finance and Operations and treasurer of the college, the decision to direct resources to pay off debt was intentional and beneficial.

“We were paying down debt. We made an intentional decision to reduce that debt,” said Clemons. “We restructured the debt, we shortened the term, […] got a lower interest rate, and we said ‘we’re going to pay down debt.’”

In 2017 the Higher Learning Commission (HLC), one of six regional institutional accreditors for colleges and universities here in the U.S., challenged Jewell’s endowment draw practices and placed the College on probation. The HLC gave Jewell a condition to regain full accreditation: the College had to reduce its annual endowment draw to 5 percent annually.

In the words of the HLC, the College was required to make changes to their fiscal policy in early 2019 ahead of a probationary status revaluation in Nov. 2019.

The HLC’s ruling was challenged by Jewell officials who believe endowment spending data was not evaluated holistically and, in response, the HLC reexamined the case, reissued a probationary notice – with updated justifications for the probation ruling – and accelerated their timeline.

The updated action letter from the HLC, issued July 17, 2018, outlined updated next steps for the college – if Jewell could provide documentation showing that its endowment draw was down to the industry standard of 5 percent by Oct. 1, 2018 then the HLC would reconsider the institution’s accreditation status in July 2019.

Jewell succeeded in meeting that goal.

Yet, ahead of the upcoming verdict from the HLC, the question is begged: what was going on with Jewell’s endowment? The answer to this question requires a holistic look at what the endowment is and why College officials chose to draw from it at a rate exceeding the industry standard.

The endowment – which could be likened to a savings account – is made up of large donations to the College and other major gifts. These can come in the form of property and industry, as well as monetary donations. This financial capital is invested into different assets, which increase in value over time, this increase in value is seen as returns for the institution.

In Jewell’s case, approximately three quarters of the endowment is invested primarily in traditional stocks and bonds through a contracted money manager. The other one quarter is invested in – what is broadly referred to as – real estate, specifically royalty interests in oil and gas in Texas, and a former golf course in Liberty, Mo. Both of these assets were gifted to the College.

The returns gained by Jewell through investing the endowment – for example, money gained from selling stocks or royalty interest on the gas and oil produced – is invested

Jewell also benefits from large non-endowed gifts that support long-term investment projects include building the Pryor Learning Commons, renovating Mathes Hall and constructing a new athletic facility.

As well as the endowment, colleges have an operating account – comparable to a checking account – which is funded through tuition payments, fees, grants and annual donations to the Jewell Fund that the institution receives. This money goes towards daily operating expenses, including utilities and employees’ salaries.

Money remaining in the operating account at the end of the financial year may be directed into the endowment fund. Alternatively, through fiscal year 2017, any deficits existing after operating expenses have been paid are covered by the endowment despite that not being its primary purpose. Due to decisions made in 2018, the endowment will no longer be used to cover these deficits.

That seems pretty simple. However, what also must be acknowledged is that most colleges in the U.S. have very large debts. Often times this debt comes from overspending on the development of campus buildings and facilities. For colleges founded in the 19th and 20th centuries it is even likely that this debt was incurred well before the current policies surrounding the institution’s finances were instated.

While institutions borrowing funds to spur development isn’t necessarily a red flag, how an institution manages its debt can be.

In the U.S. colleges and universities collectively owe $240 billion – and this debt must be accounted for. According to researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, American institutions of higher education annually spend, on average, nine percent of their operating budget servicing debt.

Having to commit so much of their operating budget to

“Instead of taking on more debt like other places did, we took more out of the endowment,” said Clemons.

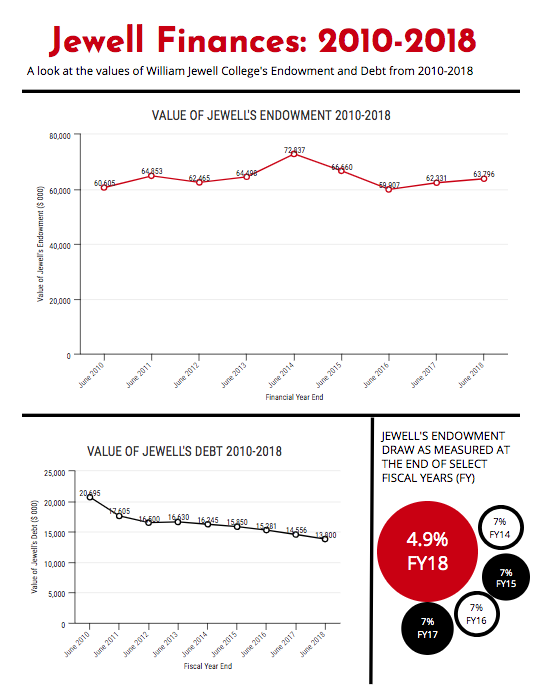

Though contested by the HLC, this decision has resulted in a decrease in Jewell’s debt from $20,695,000 in 2010 to $13,800,000 in 2018. That means the College was able to decrease its debt by almost $7 million over an eight-year period – oweing an average of close to $875,000 less each subsequent year.

Over that same period of time, Jewell’s endowment has changed from $60,605,000 in 2010 to $63,796,000 in 2018 – a net increase of over $3 million.

That means that Jewell’s current endowment-to-debt ratio is close to 5-1 – an extremely healthy measure. At its lowest in 2010, the endowment-to-debt ratio was 3-1 meaning that over the years the College has successfully reduced money owed while still increasing money available.

Despite the positive outcomes of the decisions made regarding Jewell’s endowment, challenges by the HLC were likely the result of this being an atypical tactic for institutes of higher education.

Whereas in personal finances it is typical for people to pay off their debt as soon as possible so they are more financially healthy in the long-run, many businesses and organizations choose to maintain a higher level of debt so that more money can be devoted to day-to-day expenses. Jewell’s spending policy indicates more of a focus on the long-run and the financial future of the College, rather than daily operations.

Decisions about the College’s endowment are made by the Board Investment Committee chaired by Board of Trustees (BoT) member Robert Gengelbach. Full committee approval is required for any decision regarding the endowment and – while the committee is made up entirely of BoT members – a faculty member is consulted about these decisions, typically before voting is conducted.

The current faculty member on the Investment Committee is Dr. Kelli Schutte, Department Chair of business and leadership. Faculty representatives are selected from the Faculty Council and serve for the entirety of their term on the Council – typically three years.

Utilizing a divide and conquer strategy, faculty are assigned to a BoT committee that matches their field of expertise. With Schutte’s background in business and finance it makes sense that she is serving as the faculty representative on the Investment Committee.

“I sit in on all their meetings, and I will sometimes get questions from the chair, and he’ll ask me, you know, what do faculty members think of this or that. But, I don’t vote,” said Schutte. “The way things are set up […] is to facilitate information flow, it is not a control mechanism or a responsibility mechanism.”

The board is ultimately responsible for the endowment and how that helps the college operate, including decisions regarding investing endowment assets and drawing from the fund.

Despite the struggle endured between the HLC and Jewell due to the College’s distinct use of endowment funds, the institution’s financial future is strong and – with less debt than many other colleges – established for years to come.