Since August of 2020, a group of dedicated student researchers, under the guidance of Dr. Christopher Wilkins, associate professor and chair of the department of history at William Jewell College, has been researching the history of slavery in relationship to Jewell. The research group that the students and Wilkins created, the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project, had its origins in an introductory history seminar last fall. This semester, Project members mainly convene during the HIS 204: Slavery, Memory, and Justice course that Wilkins teaches. They plan to conduct research for as long as it takes to bring the truth about the College’s relationship with slavery to light. This will ultimately conclude with the group publishing their research – writing a more accurate account of Jewell’s history in the hopes of creating a more inclusive college community.

As the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project compiles and verifies their research, The Hilltop Monitor will publish their findings. This is the first in a series of investigations into the history of slavery at William Jewell College.

In 1849, leading Missouri Baptists garnered enough money to establish the college they’d been planning for more than a decade. The only question left was where the college should be constructed. Many counties in Missouri wanted the prestige of a new, Baptist-centered school, and in August of 1849, a group of Baptists and prominent non-Baptist men met in Boonville to decide the fate of the school.

There was much debate on where to establish the college, and several Missouri counties competed for the college. Despite a large gift of $7,000 (approximately $240,797 in today’s money) from the citizens of Clay County to the college’s endowment, Liberty did not yet have the majority of the votes. It was Alexander Doniphan’s “brilliant and enthusiastic speech” that ensured the college would be built in Liberty, Missouri, and named after Dr. William Jewell.

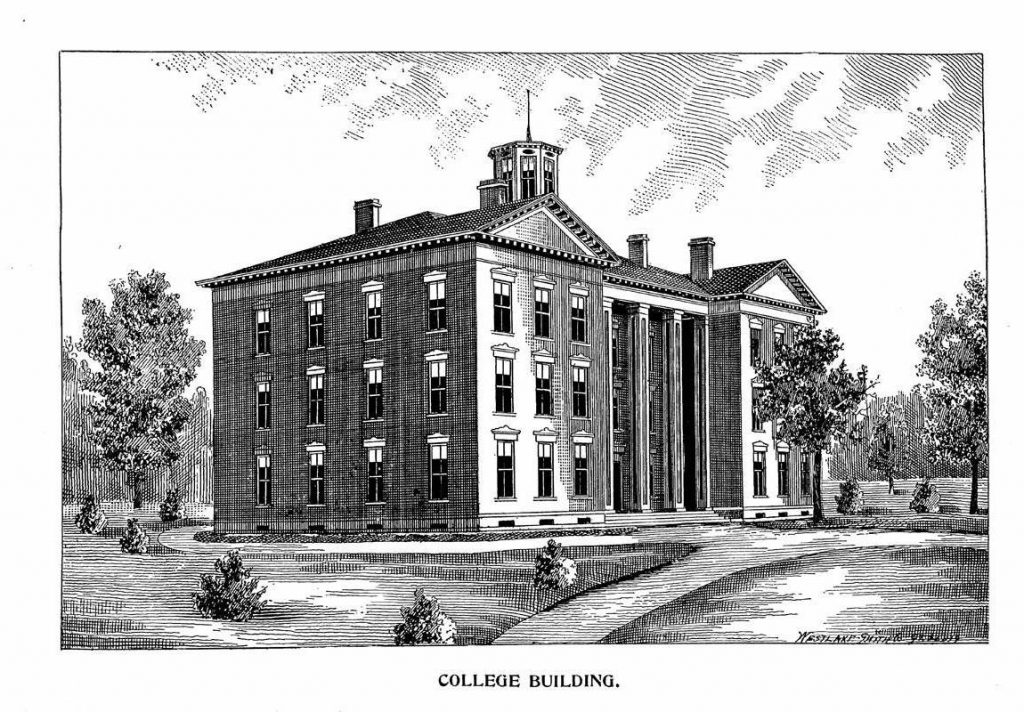

Construction on Jewell Hall began in 1850. Classes were held in rented rooms in Liberty in January of 1850, the same year that construction on Jewell Hall began. Classes began meeting in the building, the oldest building on the campus, in 1853, and it was fully completed in 1858.

Wealthy farmers, bankers, lawyers, doctors, ministers and politicians made up the founders and trustees of Jewell. Notable founders include Jewell and Doniphan, who were responsible for the funding and location of Jewell; James T.V. Thompson, who donated the land for Jewell; Roland Hughes, the first president of the Board of Trustees; and Wade M. Jackson, Jesse E. Bryant, David H. Hickman, and R.E. McDaniel, the second through fifth presidents of the Board of Trustees, respectively. W.C. Ligon, another trustee, was also crucial in bringing the college to Liberty and raising the funds for the college in its early years.

There were 33 total original founders and trustees of William Jewell College from 1849-1850, as detailed in James G. Clark’s 1893 “History of William Jewell College.” Of the 33 earliest trustees, Clark lists 26 as “charter members” and seven who joined the Board of Trustees in 1850 as “additional members.” However, the seven additional members were vital to the founding and building of Jewell and are thus being included with the others as founding trustees.

This part of William Jewell College’s history is well-recorded and celebrated in many different history books. What is virtually not included in these histories is the relationship that the early founders and trustees had to slavery.

Of the 33 early trustees, 90% of them were slaveholders.

By looking through slave schedules and census records, Wilkins determined that the 1849-50 trustees held, at minimum, 307 enslaved people. Only three of the 33 founders did not directly own enslaved people. Two of them may have directly benefitted from slavery, but there is insufficient evidence to prove such. The third, R.R. Craig lived in a household that owned 16 enslaved people and benefited from their labor.

Between 1851 and 1865, 24 additional trustees joined the board of William Jewell College. Of the group of 24, 19 were slaveholders. Wilkins found that this group owned a minimum of 153 enslaved people. Two of the five that, as far as research shows, did not personally own enslaved people, lived in slaveholding households.

According to the research of the Project members, the founders and trustees owned more than 400 enslaved people. These founders directly benefited from the exploitation of enslaved people and used, at least in part, the profits from their forced labor to fund the College.

Stephen, Ellen, Emmanuel, Nelson, Harrison, Steven, Emory, John Anderson, Joe Decoursey, Maria Decoursey, Hannah Coger, Samuel, Polina, Merit Withers, James Moss, Joseph Hughes, Alexander Trant, John Trant, Lewis Washington, Benjamin Carr, Moses Combs, and Washington Combs.

Those are the names of 22 enslaved people who were owned by William Jewell College’s founders and early trustees. There are more than 380 names of people enslaved by the early founders and trustees yet to be found. The Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project will work to find as many of their names as possible.

Beyond the founders and trustees, Jewell’s first four presidents were all slaveholders.

Rev. E.S. Dulin, president from 1850-52, owned one enslaved woman in 1850. Rev. R.S. Thomas, who was president from 1853-55, owned six enslaved people in 1850. The third president, Rev. William Thompson, owned two enslaved people in 1860. Rev. Thomas Rambaut, president from 1867-74, owned two enslaved people as of 1850.

Wilkins found evidence that Dulin and Thompson, the first and third presidents, respectively, owned enslaved people while serving at the College.

None of this history could be found in the William Jewell archives – which couldn’t be accessed by students this year because of COVID-19 – or the three published histories of the College. In fact, in the three books about William Jewell College, slavery or some iteration of the word is mentioned only five times.

Slavery is mentioned just once in Clark’s 1893 “History of William Jewell College” when talking about Dr. Adiel Sherwood, whose father owned enslaved people. Sherwood helped raise funds, more than likely including wealth from slave labor, for an endowment for William Jewell College. For this gift, a departmental chair was named after him.

In “Jewell is her name: a history of William Jewell College,” written by Hubert Inman Hester in 1967, there are two references to slaves. Both references discuss Dr. William Jewell owning enslaved people and later manumitting some and freeing the rest in his will. Jewell did own at least 5 enslaved people in 1850 and manumitted some during his lifetime.

But the idea that he freed all of them in his will is not true.

One student researcher, Christian Santiago, found that Jewell manumitted nearly all of the enslaved people he owned in his will – except for one. Ellen, an enslaved woman, would only be freed upon highly specific conditions. Even then, any children she had would be kept in slavery. These details will be discussed in a later article.

The most recent history of the College – “Cardinal Is Her Color: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Achievement at William Jewell College,” published in 1999 by William Jewell College – mentions slavery twice.

The first reference discusses the now disproved notion that Jewell freed all the enslaved people he owned upon his death. The second reference discusses the now-disbanded Beta Xi chapter of Sigma Nu, which formed at the College in 1894. The Sigma Nu chapter moved into the Major Alvin Lightburne house on The Liberty Square in 1899. The house, according to the book, was rumored to be part of the Underground Railroad. The Project has been unable to find any evidence to substantiate this claim.

None of these history books, all of which are linked on Jewell’s website, discuss slavery much at all. Information on the extensive slaveholding of nearly all of the early founders, trustees and presidents – which is detailed in primary documents from the time – was never included in the official histories or mythologies related to the College.

Wilkins and his class located, gathered and substantiated this information. The fact that over 400 enslaved people were somehow tied to the founding and early years of the College cannot be stated enough. The five early founders and trustees who owned the most slaves were among the largest slaveholders in Missouri. James T.V. Thompson, who owned the land upon which Jewell now sits and donated it to the College, held 39 people in slavery in 1850, making him the largest slaveholder in Clay County.

The story of William Jewell College – one of the oldest colleges west of the Mississippi River – is one that is inextricable from the brutal institution of slavery. This history has not been suppressed or erased, it’s never been written.

Those students involved with the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project will continue to work to bring the truth about William Jewell’s past to light. The group will be presenting the research they’ve done up to this point April 23 at Jewell’s David Nelson Duke Colloquium.

The College is now implementing a Racial Reconciliation Commission, to tell the truth about the racial history of the College from its founding until today. The student-led Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project is operating independently of the Commission and focusing its attention on Jewell’s early relation to slavery, rather than later eras in the College’s history.

Wonderful research to discover this history.

Just a note of appreciation for your work. The collaborative genealogy website, Wikitree, is starting to document Black genealogy. At present they have not yet covered Clay County. I am writing you because my great-grandfather, Robert Hugh Miller, founder and publisher of the Liberty Tribune (see his name in Wikipedia) held a few household slaves and was probably a trustee of William Jewel. As a small child I was taken to visit his daughters in Liberty, my grandaunts. With them was an old lady who had been born in slavery and stayed with the family. I have later wondered if she was their half-sister. I regret that I have been unable to recall her name.