A protester holds up a sign in reference to the sex abuse scandal within the Catholic Church as Pope Francis travels through the city in the Popemobile on Aug. 25, 2018, in Dublin, Ireland.

On Nov. 12, Pope Francis once again delayed the process to address the pervasive problem of child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church. The bishops from each of the 196 archdioceses in the U.S. were scheduled to meet to vote on measures to confront the child sexual abuse crisis when, in the first few minutes of the meeting, a message from Pope Francis was relayed – asking the bishops to withhold their votes until the Pope could lead an international meeting of church leaders in February.

This continuous refusal by Church authority to swiftly and effectively address child sexual abuse is undoubtedly due to a systematic failure. A failure, firstly, by church officials and institutional Church leaders within the Church to report egregious acts of priests who utilize their station to abuse the most vulnerable members of their congregations. Secondly, the primary failure I will examine in this article, is that of the Church authority to legitimately reform the institutional structure of the Church in order to stem the problem at its source so that there is no impetus to cover these crimes up in the first place.

Unique to Catholicism among Christian denominations is its strong regulatory body, centralized in Vatican City in the personhood of the Pope. This central authority facilitates the Church’s unique ability to maintain harmonious and collective action among its members. Given this potent capacity, the Church, especially those in the highest positions of its institutional structure, has the power to wholly reform its structural integrity – to root out morally questionable features in order to be as pure as possible.

Before I begin it is probably necessary for me to acknowledge the obvious fact that only a small percentage of priests have sexually abused children. Still, just because this number is small does not mean it is negligible or that the problem can be resolved by simply removing or rehabilitating the priests who’ve committed these crimes. Child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church is a well-known and all too prevalent problem to be solved with one of these quick fixes.

The purpose of this editorial isn’t to question the theological validity of the Church. Theologically and spiritually, the Catholic Church has a religious right to practice and worship in ways that don’t constitute harm. Furthermore, Catholicism’s modes of worship and dogma are not what spur the prevalence of sexual abuse within the Church; in fact, the most fundamental Catholic beliefs utterly oppose these acts. Rather, I argue that there is an institutional culpability in this egregious instance of moral decay in the Catholic Church.

I can sit down and write thousands of words about the moral decay I see present in the Catholic Church, but simply writing down what is wrong won’t do anything to fix it. So, I will present my argument for the proper response to the state of the institution. I argue for the overhaul of the institution of priesthood. I propose two key changes that can be made to the institution of priesthood to root out the moral corruption within.

1.) Allow priests to be fallible.

Priests aren’t – nor should they be – Jesus incarnate. Allowing priests to be viewed both by congregations and by Church administration as humans capable of making poor decisions will remove impetus to cover up their missteps and remove the overwhelming pressure upon priests to obfuscate their inevitable struggles with temptation. By not expecting total infallibility, struggling priests could turn to legitimate sources of help for their turmoil and struggles with sin rather than letting troubling inward feelings mutate into horrific acts.

Removing the requirement of celibacy for priesthood could be a valuable initial step to minimizing sex abuse. This is a prospect Pope Francis is seriously considering – he referred to the practice of celibacy as simply “discipline, not dogma.”

Placing the expectation of celibacy on priests is unnecessary and, according to a 1985 study, the leading deterrent of young men from joining the priesthood. The removal of such an expectation is a prospect already supported by 71 percent of the U.S. Church laity and 51 percent of American priests.

It is not unreasonable to examine the role of the celibacy requirement in the motivation of priests’ to sexually abuse children. For a tempted, already morally unstable priest who feels the need to release his sexual frustration, targeting children would be the least risky way to give in to the temptations. Since children are vulnerable and relatively powerless, they won’t have the means or understanding to report the crime, and if priests convince them that the abuse is something they cannot talk about with others – an easy proposition to sell, since Catholic children are taught of priests’ religious authority from a young age – they can commit these horrific acts while still retaining the appearance of a celibate priest.

Photo courtesy of Stop Abuse Campaign.

The solution to this crisis, however, is not a responsibility of members of the priesthood alone. The institutional framework of the Church – including Church administration, all the way up to the papacy – systemically facilitates the obfuscation of egregious acts committed by priests. This obfuscation enables morally bankrupt priests, who are essentially immune to social or legal punishment through the powerful shield of Church officials.

All too often, due to an intentional failure on the part of Church officials, whether it be diocesan leaders or Vatican authorities, it is a secular source that reveals this corruption. The most recognizable example of this, and the subject of the 2015 Best Picture Academy Award-winning film “Spotlight,” is the revelation of rampant child sexual abuse – and consequent cover-ups – among Roman Catholic priests and laypeople in Boston, Massachusetts, by a local newspaper – The Boston Globe.

This was reiterated most recently in Pennsylvania, when law enforcement opened an investigation into Pennsylvanian dioceses after reports of sex abuse – spanning over several decades, with an alleged victim count in the thousands – that was covered up by diocesan leaders. This is the first investigation led by the federal government of a Roman Catholic sex abuse case.

Dismantling the false appearance of infallibility will make Church authority less hellbent on covering up priestly failures, perhaps making them more likely to report crimes within the Church to law enforcement, who – as a necessarily secular entity – can adequately serve justice.

The Church’s biggest mistake has been refusing to address the issue in fear of devastating effects on its own reputation. Presumably, Church officials fear the demise of the Church as we know it if they come clean about this crisis, so they construct illusions of infallibility to shield themselves from being deemed hypocrites, further entangling themselves in webs of contradictions that are so knotted up, the integrity of the Church will be utterly unsalvageable.

2.) Expand the criteria by which people may become priests.

Most importantly, the Church should open up priesthood to women. The immense pressure on priests to cover their duties in the face of a shortage of people to fill the vocation undoubtedly allows people who are unfit to be bestowed with the precious authority that they don’t have the responsibility or moral aptitude to use correctly. In Nov. 2017, Pope Francis raised the prospect of admitting married men into the priesthood as a way of covering for the shortage of priests in the Church.

Photo courtesy of The Denver Post.

While I think this is an apt approach in both covering for the shortage and minimizing sexual deviance among members of the priesthood, I find this relaxed standard to be hypocritical, considering the Church’s unchanging opinion on women in the priesthood.

In 2013, Pope Francis reinforced the Church’s exclusion of women from the priesthood, saying, “with regards to the ordination of women, the church has spoken and says no … That door is closed.” The majority of American Catholics, however, disagree, with 59 percent saying they favor the ordination of women in a 2010 poll. When Pope Francis reaffirmed his position in 2018, he explained his position, arguing that the exclusion of women from the priesthood is not a discriminatory tradition, that, in actuality, it is based in Catholic dogma.

This supposed dogma is based simply on the fact that Jesus’ apostles, and their successors, were all men. The historical context, however, is ignored here. In order for the Catholic Church to spread and enlighten according to its proper course, male leadership was necessary to attach legitimacy to the faith. As the association of femaleness with illegitimacy in authority has weakened over time, the Church should restructure the priesthood to reflect this social change.

This isn’t about “liberalizing” the Catholic Church. The only agenda I have in proposing that the pool of people who are able to serve as priests is the eradication of sexual abuse within the Church. This is, at its core, an endeavor that is essential to the moral viability of the Church. It is also an endeavor that requires the transformation of the Church’s structure.

The perpetuation of child sexual abuse is deeply intertwined in the Catholic Church’s tie to tradition. Because tradition is such a significant part of the Catholic faith – and religion in general, the idea of making significant changes to the structural composition of the Church seems like a potentially risky and irreversible decision that should be avoided at all costs. Instead of navigating the intricate task of excising moral corruption all the while preserving the holy traditional rite of the Church, leaders turn instead to duct-tape solutions that address immediate concerns but don’t attack the root of the problem.

I don’t want to leave unacknowledged the extreme difficulty of adequately handling situations of this caliber. On one hand, the Church authorities have to be concerned with the reputation of the Church – with ensuring that corruption in the priesthood is contained and eliminated to the best of their abilities, with appropriately administering the core virtue of forgiveness when dealing with priests who commit atrocious acts. On the other hand, the Church needs to ensure its own legitimate moral uprightness – there is no room for such outright examples of moral corruption in an institution that seeks moral purity.

For Church officials, a few important trade-offs emerge, and I believe these are what produce the disconnect from Church higher-ups and angry observers: At the expense of appearing as if we permit the commission of significantly immoral acts, do we do our best to work with and rehabilitate culpable priests in the name of forgiveness and compassion? If we immediately remove priests from their stations, could the Church’s existence be threatened? If we admit that there is a problem with child sexual abuse within the Church, will the reputation of the Church be irreparably tarnished?

Pope Francis was celebrated for being an anomalously progressive pope, mainly for his decision to let Catholic social teaching – a doctrine based on the New Testament that promotes the upholding of the dignity of all God’s creation – guide his social initiatives, seen most clearly in his publication of the encyclical “Laudato Si,” which involved the unprecedented acknowledgment of climate change, global warming, consumerism and Catholics’ duties to protect the Earth from these crises.

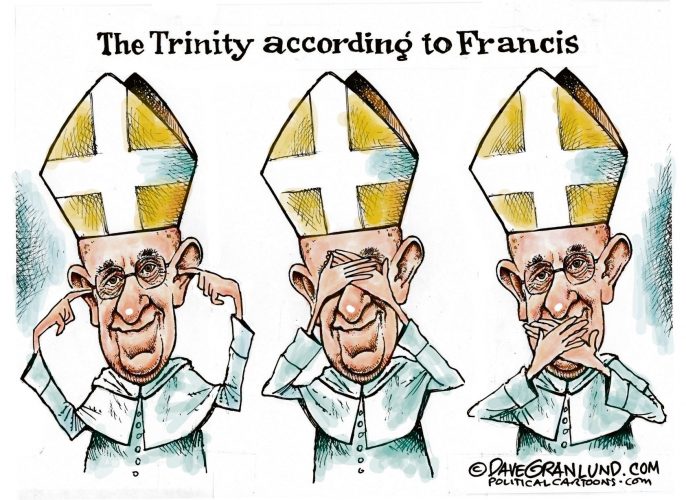

Still, it is incorrect and hypocritical to praise Pope Francis for extending the Church into a new, progressive era when he still refuses to adequately reform the institutional structure – the domain of which he is explicitly in charge – in order to address the most egregious and imminent offenses that have resulted from the complacency and ignorance of previous popes.

Moreover, though some point to authorities on lower levels of the Church hierarchy as the reasons why plans to address the crisis have failed, the unpopular papal decision to delay problem-solving discussions Nov. 12 has proven otherwise.

Several bishops expressed their disappointment with the Pope’s decision, taking issue with the lack of urgency with which the Vatican has been treating the situation. There is overwhelming support by bishops, priests and other clerical members for quick and strong action against this crisis, but all of it falls on the deaf ears of Pope Francis, the sole figure in the Church structure who has the power to begin this intensive Church overhaul.

Photo courtesy of St. Louis Today.

Pope Francis refuses to accept the intense, arduous role of the theological surgeon. He has a duty to carefully excise this metaphorical cancer within the body of the Church while keeping its integrity intact. As he denies its severity and refuses to perform the extraction, the cancer only metastasizes. Unacknowledged, it will destroy the Church in totality.

Ultimately, the power lies in the papacy to effect meaningful, successful and long-term eradication of the pathology present in the priesthood – but this power clearly hasn’t been realized by the one person who needs to realize it.

This problem is imminent. It is recent. It is current. It is constant. There is no time to wait for another encyclical that explicitly decries sexual abuse. Most importantly, there is no time to wait until February before even the simplest of discussions begin to root out this most egregious atrocity that the Church itself has perpetuated. To appropriate the words of Pope Francis in “Laudato Si,” this crisis demands “swift and unified global action.”

So, the question must be asked: What’s keeping Pope Francis from calling for a widespread and thorough investigation into the priesthood?

To understand the answer to this question, one must also understand that the Church is experiencing a sincere threat to its sustainability – members of monastic life, especially the priesthood, have dwindled significantly. Younger people are continually gravitating away from the Church. Presumably, the Pope fears a massive blow to the Church’s reputation that public acknowledgement, deep investigations and quick, reckless response could engender.

These fears are negligible, however, when considered in context of the crisis from which they arise. No child should be molested as a sacrifice for maintaining a robust priesthood. One child saved from a lifetime of trauma is worth the elimination of thousands of priests from the priesthood. What’s more, the continued protection of children from sexual abuse is absolutely contingent on the thorough overhaul of the Church’s institutional structure.

The Church will be tested. The priesthood will dwindle. The Church’s reputation will be damaged. But these setbacks ultimately pale in comparison to the spiritually necessary promises of justice, reparation and purity that lie beyond them.

Photo courtesy of Charles McQuillan, Getty Images.