Since August of 2020, a group of dedicated student researchers, under the guidance of Dr. Christopher Wilkins, associate professor and chair of the department of history at William Jewell College, has been researching the history of slavery in relationship to Jewell. The research group that the students and Wilkins created, the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project, had its origins in an introductory history seminar last fall. This semester, Project members mainly convene during the HIS 204: Slavery, Memory, and Justice course that Wilkins teaches. They plan to conduct research for as long as it takes to bring the truth about the College’s relationship with slavery to light. This will ultimately conclude with the group publishing their research – writing a more accurate account of Jewell’s history in the hopes of creating a more inclusive college community.

As the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project compiles and verifies their research, The Hilltop Monitor will publish their findings. This is the third in a series of investigations into the history of slavery at William Jewell College.

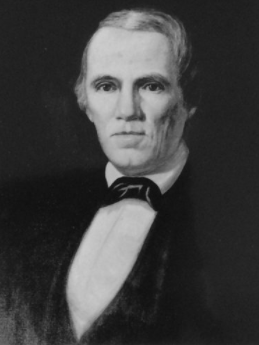

Dr. William Jewell was deeply committed to higher education and used his influence in civic and political affairs to assist with and lead several educational initiatives. Jewell was a member of the Board of Trustees for Columbia Female Academy, the first school for women west of the Mississippi River. He personally donated $1,800 and assisted with the grassroots fundraising for the location of the University of Missouri in Boone County.

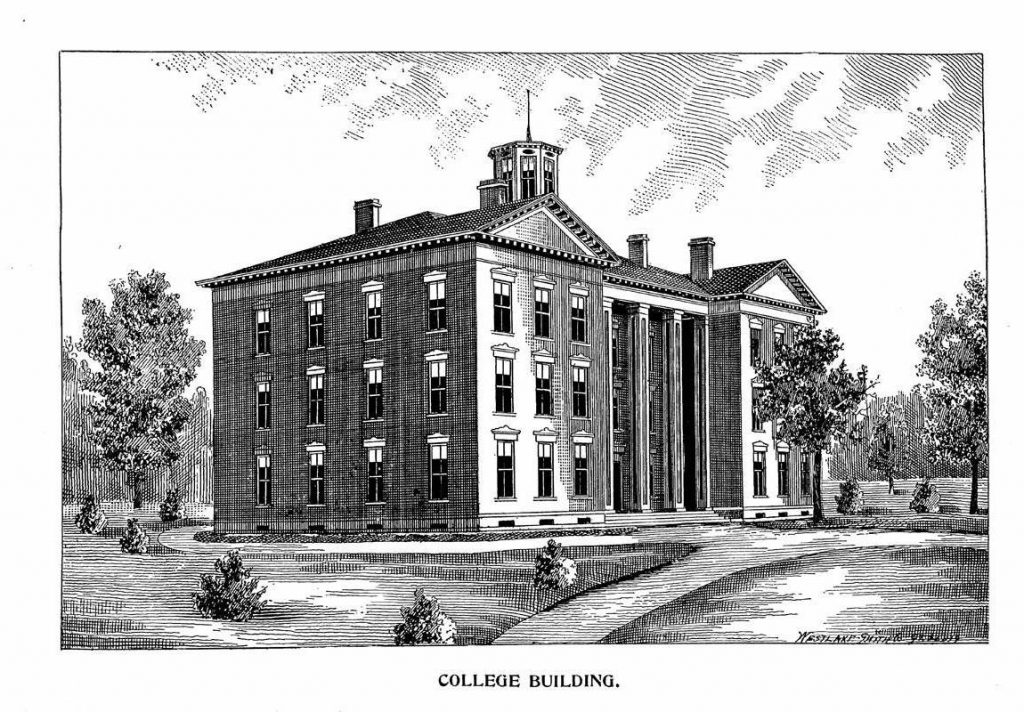

In 1849, William Jewell donated $10,000 worth of land towards founding the first all men’s Baptist institution west of the Mississippi River, further demonstrating his dedication to the pursuit of knowledge. In recognition of Jewell’s gift, Missouri Baptists named the college in his honor. The details of the college founding are covered in greater depth in the first two installments of this investigation.

Jewell’s dedication to higher education, philanthropic ideals, and work as a physician and legislator is well-recorded and commended in a variety of different and easily accessible historical sources. These historical accounts, however, only briefly mention Jewell as a slaveholder – if at all. The accounts that do mention his ties with slavery often discuss it in a way that minimizes the significance of his slaveholding by focusing on the eventual manumission of most of the enslaved people he owned.

In “Jewell is her name: a history of William Jewell College,” written by Hubert Inman Hester in 1967, there are two brief references to Jewell owning enslaved people. Rather than focusing on the economic benefits Jewell derived as a slaveholder, Hester elects to focus on Jewell’s decision to manumit all of the enslaved people he owned by the time of his death. Hester praises this as evidence of Jewell’s “interest in people.”

In similar fashion, the most recent history of the College – “Cardinal Is Her Color: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Achievement at William Jewell College,” published in 1999 by William Jewell College – mentions that Jewell freed all the enslaved people he owned upon his death.

In a 2015 Hilltop Monitor article, “Who Was William Jewell,” a student writer continues this narrative and incorrectly describes Jewell as an abolitionist. The article, written with information found in the Charles F. Curry Library archives, notes that though Jewell initially owned enslaved people, he emancipated four of them in 1846 and granted freedom to two in his will.

These accounts of Jewell as a slaveholder make Jewell seem like a gentle man whose slaveholding was benign and even good. The research done by the Slavery, Memory and Justice Project has discovered that:

- Jewell owned more enslaved people than the College sources have indicated.

- Jewell did not unequivocally free all the enslaved people he owned.

- Jewell’s actual record regarding slavery is more complicated than current narratives portray, and claims that Dr. Jewell was anti-slavery must be reevaluated.

The Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project researchers, using Federal census records, determined that Jewell owned 13 enslaved people in 1830, six enslaved people in 1840, and five enslaved people in 1850.

Christian Santiago, sophomore history and political science major, has done significant research in the past year. While visiting the Boone County archives, Santiago uncovered a history of Jewell that is not currently reflected in the accounts of the College and its namesake.

In his research, Santiago found that Jewell manumitted the enslaved people he owned in his will – except for one: Ellen. Rather than freeing her, Jewell provided that Ellen would remain enslaved, first under the ownership of his sister, and then under the control of his grandson after he reached the age of 21. Jewell did include a provision that Ellen would be freed if his grandson died before turning 21, but any children she had would remain enslaved.

Glancing around the campus, Jewell’s legacy is ubiquitous. From signs to buildings to student sweatshirts, Jewell’s name has been immortalized. There is no recognition, however, for the individuals owned by Jewell who were an integral part of the financial impact that Jewell had on the school. These enslaved individuals were silenced and, until recently, their names were unknown.

While there are still more names to track down, the Slavery, Memory, and Justice project has identified the names of seven of the individuals held in slavery by Jewell.

Ellen, Emanuel, Henry, Mandy, Phillis, Ralph and Stephen.

Jewell was also the president of the Missouri Colonization Society – a branch of the African Colonization Society.

In an article from the Missouri Historical Review titled “Persistency of Colonization” by Donnie D. Bellamy, the racist roots of the American Colonization Society are revealed. This group wanted to remove free Black people from the United States and resettle them in Africa.

While this group has been referenced as an anti-slavery organization, Bellamy’s article explains that some members of the American Colonization Society saw the organization as pro-slavery, as the removal of free Black people from the country would strengthen slavery. Many African Americans were highly critical of the organization due to the nearly all-white composition of its leadership, the support it garnered from some slaveholders and its denial of free African Americans’ right to stay in the country they played such an integral role in building.

Jewell’s history is a complex one. His dedication to education and the community is clear and is worth recognition. His eventual emancipation of most of the enslaved people he owned is also significant.

However, as Santiago explains, this does not erase his status as a man who benefited from the institution of slavery for decades.

“Even if you choose to view his actions with his slave Ellen or his involvement with the African Colonization Society as some sort of justifiable paternalism, the fact remains that he was aware of abolitionist and other anti-slavery narratives of his time but still actively played into our chattel slavery system,” said Santiago.

The narrative that the College has of Jewell is incomplete. Jewell’s status as a slaveholder and the complexity of his actions regarding slavery have not been accurately reflected in our history. This abridged history of Jewell is what the Slavery, Memory and Justice Project is dedicated to addressing.

Santiago addresses the urgency of continuing this research.

“As members of this community, we inherit the namesake of William Jewell as our own and must choose whether to reject it, ignore it or do something meaningful about it,” said Santiago. “I choose to believe that significant progress can only be made through this final option. Especially as an institution that prides itself on an emphasis on critical thought and inquiry, it would be ignorant of us to subscribe to certain symbols and the legacy of certain individuals if we could not rationalize why we do so. ”

Jewell and his legacy are intrinsically tied to the school – in more than just a name. As Santiago explains, our legacy is bound to Jewell’s. If we claim to uphold the mission of our school, Jewell’s past with slavery needs to be confronted.