Since August of 2020, a group of dedicated student researchers, under the guidance of Dr. Christopher Wilkins, associate professor and chair of the history department at William Jewell College, has been researching the history of slavery in relation to Jewell. The research group that the students and Wilkins created – the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project – had its origins in an introductory history seminar held last fall. This semester, project members primarily convene during the HIS 204: Slavery, Memory, and Justice course that Wilkins teaches.

The project plans to conduct research for as long as it takes to bring the truth about the College’s relationship with slavery to light. This will ultimately conclude with the group publishing their research – writing a more accurate account of Jewell’s history in the hopes of creating a more inclusive college community.

As the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project compiles and verifies their research, The Hilltop Monitor will publish their findings. This is the second in a series of investigations into the history of slavery at William Jewell College.

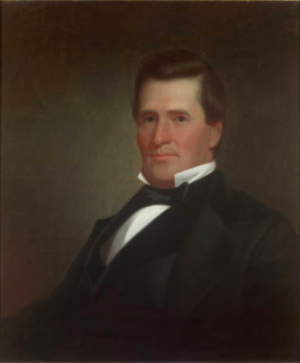

Alexander Doniphan, one of the most influential Clay Countians, played a key role in the founding of William Jewell College. While Doniphan is not as well known as Dr. William Jewell, his contributions to the College are unmatched.

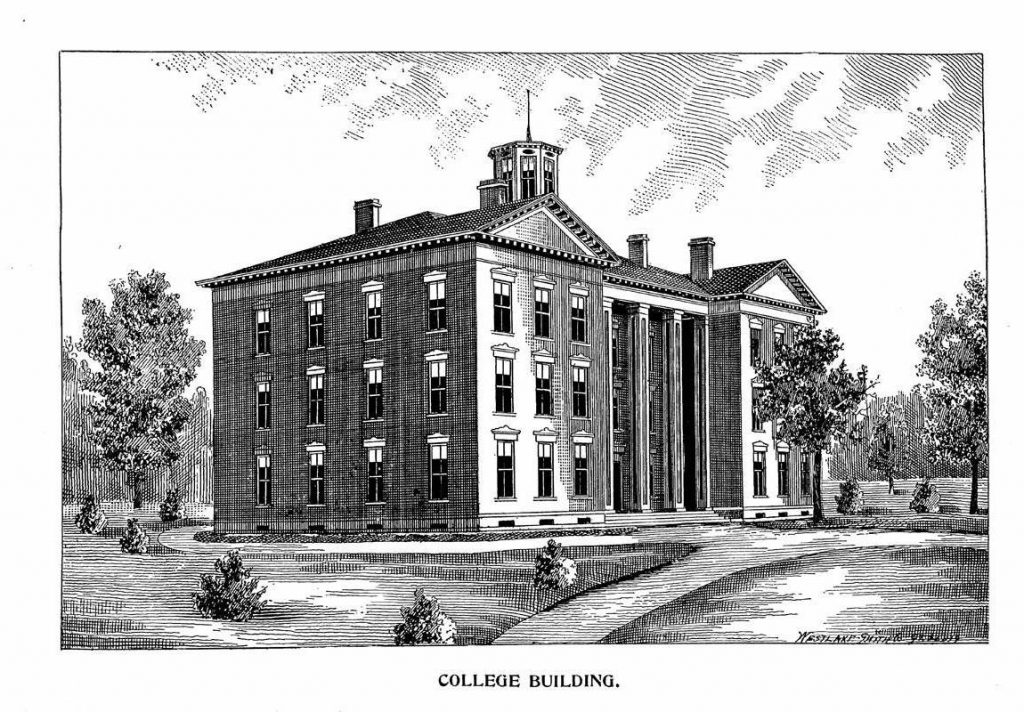

In 1849, Baptist leaders met in Boone County to discuss the location of a new Baptist college in Missouri. Doniphan’s famed oratorical skills and $7,000 – the equivalent of over $240,000 today – he helped raise from the citizens of Clay County secured Liberty as the College’s new home and helped ensure that the new institution would be named after Jewell. Thus, William Jewell College was born.

Doniphan is also celebrated for his bravery in defense of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1838, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs issued the Mormon Extermination Order. Missouri Militia Major General Samuel Lucas captured Latter-day prophet Joseph Smith and other church leaders and sentenced them to public execution for treason, a sentence Lucas ordered Doniphan to carry out. Doniphan refused the order.

“It is cold-blooded murder. I will not obey your order… If you execute these men, I will hold you responsible before an earthly tribunal, so help me God,” Doniphan said.

People have viewed Doniphan’s saving of Smith and others as evidence of his willingness to stand up against popular belief and his dedication to the rule of law. The church recently renamed a local ward in Liberty after him to show their respect and appreciation.

Doniphan’s military leadership in the Mexican-American War has also been praised. He led his men on one of the longest marches in U.S. military history, winning key battles over much larger Mexican forces, and played a crucial role in the U.S. victory over Mexico. One source wrote, “None of the other campaigns — Zachary Taylor’s, Winfield Scott’s, or John C. Fremont’s — accomplished as much with such a small force or with as little difficulty.”

In the 1850s, Doniphan’s success as a defense attorney, businessman, philanthropist and member of the State Legislature continued to make him a widely respected figure in Missouri life.

Narratives focusing on Doniphan and the Civil War emphasize his support for the Union and opposition to Missouri’s potential secession. Doniphan organized Union rallies in Clay County and advocated for keeping Missouri in the Union.

He served as a delegate to the 1861 Peace Conference in Washington, D.C., which sought a compromise to keep the Union together. When secessionist Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson sought to convince Doniphan to serve as a Brigadier General in Missouri’s Confederate forces, Doniphan declined. Most Clay County citizens supported the Confederacy, so Doniphan, as a Unionist, had to stand firm against the majority opinion, which contributed to his reputation for bravery.

While the preceding information is accurate, one of the most disturbing and important aspects of Doniphan’s history – his connection to slavery – has received very little attention. That is, until now.

The research carried out by the Slavery, Memory, and Justice Project shows that slavery was not a minor element of Doniphan’s life; it was among the most central. From his earliest years until the abolition of slavery, Doniphan owned enslaved people and benefited from their labor. He used the wealth he acquired from them to give money to William Jewell College. Although he earned much of his fortune from his legal work and business investments, Doniphan greatly profited from the labor of enslaved people.

Federal census records show that Doniphan owned three enslaved people in 1840. Other sources demonstrate that he owned at least two enslaved people in the late 1840s. In 1850, he likely owned more than two enslaved people, as demonstrated by his farm’s production of 11 tons of hemp. The crop was cultivated almost exclusively by enslaved people, proving once again the economic benefits Doniphan reaped from forced labor. In 1860, census records again showed that the number of enslaved people he owned increased to five, indicating his strong commitment to the institution of slavery.

In addition to his economic stake in slavery, Doniphan’s political commitment to defending slavery was profound. In 1837, while serving in the state legislature, Doniphan supported a bill making it a crime to publicly advocate for abolition, punishable by imprisonment in the state penitentiary.

The bill as originally written would have punished violators with imprisonment in county jail, but Doniphan amended it to be the state penitentiary to further dissuade abolitionists from undermining slavery in Missouri. Doniphan also supported making Kansas a slave state – he served as a director of and donated money to the Clay County Pro-Slavery Society.

When Doniphan was a candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1854, he was viewed, according to a later account from Missouri Congressman James C. Rollins, as not only pro-slavery, but as someone whose dedicated defense of slavery had made him the “favorite” candidate for the “strongest pro-slavery district in Missouri.”

In 1861, Doniphan supported the Crittenden Compromise, an amendment that would have permanently enshrined slavery in the U.S. Constitution in exchange for ending Southern secession. In 1863, Doniphan only reluctantly endorsed the gradual emancipation of Missouri’s slaves because he feared Missouri Republicans’ plans for the immediate abolition of slavery. In July 1863, Doniphan told an audience in Clay County that even though he now supported gradual emancipation, he would always be pro-slavery “in his feelings and sentiments.”

Doniphan’s ties to slavery are exemplified through the economic benefits gained from his ownership of enslaved people and the legislation he supported to protect and expand the institution of slavery. Doniphan was deeply pro-slavery, which is important to note when honoring his legacy with statues, street names, societies, and awards.