Photo Courtesy of Ingrid Weaver

Hew Locke’s exhibit “Here’s the Thing” opened at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art Sept. 12 and goes until Jan. 19, 2020. The exhibit is a collaboration between Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, UK; Colby College Museum of Art in Maine; and the Kemper Museum in Kansas City.

The exhibit is an exploration of the global, postcolonial world, with Locke, a British-Guyanese artist, working in drawing, painting, sculpture, photography and multimedia mediums. Locke’s most powerful tool in the exhibit is the re-appropriation of colonial forms, whether it’s jewels, precious metals, statues of Queen Victoria, trading ships or stock certificates. The use of these artifacts not only harkens back to the time when they helped produce the violence of colonialism, but it also exposes their appearance today and reclaims them, using them as part of colonial critique. Hew Locke’s personal experience involves boats, cross-continental voyages and living as a colonial subject.

“Guyana means ‘land of many waters’ – you are constantly aware of boats…People want simple answers about what this work is about, but it doesn’t exist. Migration, trade, refugees, warfare, exploration, tourism…[are] extremely messy and interlinked,” said Locke in a document about the exhibit.

While Locke’s work is striking without understanding the historical particulars of colonization, learning about the specific references he makes to ships, monarchs and events open the exhibit to even wider significance. The exhibit forces one to think and experience during the viewing process, and it also leads one to further exploration of, in this case, colonialism.

Aside from his iconic ships, one of the motifs Locke works with is the bust, as seen in the Souvenir series. Like “Untitled (Orange Queen),” the “Souvenir” series features busts of monarchs, in this case Queen Victoria, Princess Alexandria and Edward VII.

Photo courtesy of Ingrid Weaver

While each of the busts is white, they are all adorned with clay skulls, gold medallions, cowrie-shells military medals, fake beads, and even lace and crowns. The result is that the busts are dripping, overly adorned with symbols of wealth. The symbolic wealth, however, is consciously fake, in appearance and in the fact of its excess, giving it a hollow, shallow quality.

Locke said the following about “Untitled (Orange Queen),” in which the head is adorned with plastic toys, fake gems and cheap fake plants to the effect of gaudiness.

“It is aspirational – in that I try to take the cheapest thing I can find and work to make it look precious. The irony here is that the material I am using – such as golden plastic toy weapons and jewelry – are trying to look expensive”

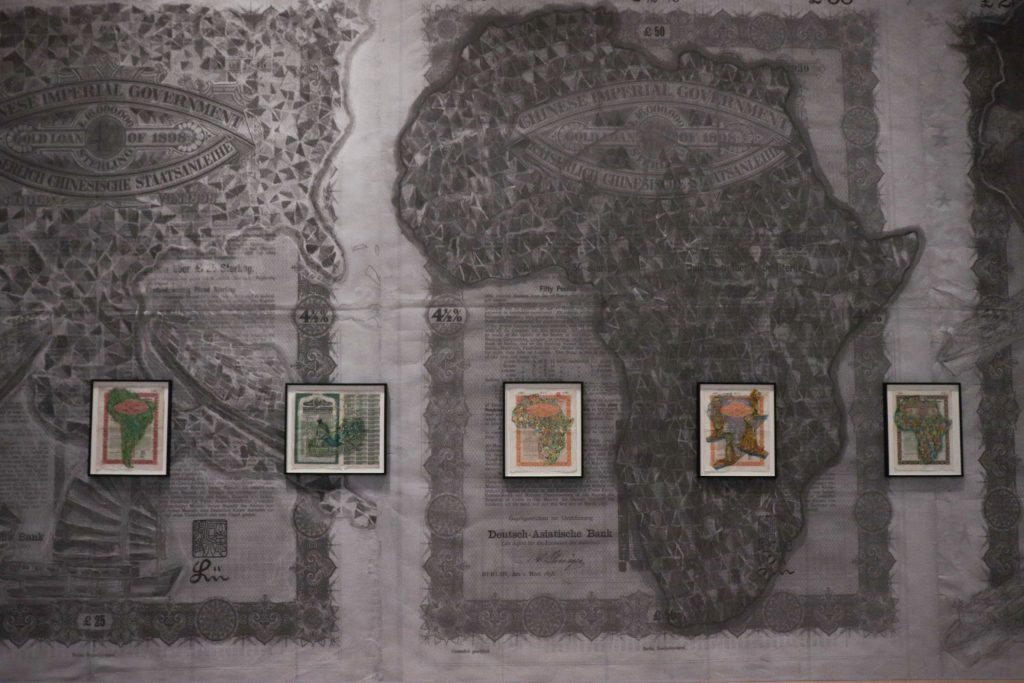

Across from the “Souvenir” series is the “Wallpaper and Chinese Imperial Gold Loan.” The wall of this side of the room is an enlarged version of an antique loan document, and on the wall are small, framed versions of these loan documents.

In one of these a painted version of Africa is overlaid on the document, painted as though it was made of jigsaw puzzle pieces. This clever and striking move points to the scramble for Africa that occurred in the heyday of colonization. The forced breaking up of Africa into mere game pieces of Europe is deftly shown in Locke’s work, coupling both historical documents with his modern work. The work’s palimpsestic quality adds another layer of meaning – emphasizing the multiplicity of identity in colonial society, the split consciousness of the colonial subject.

Photo courtesy of Ingrid Weaver

Taking up an entire room of the exhibit, Locke’s colossal installation, “Armada,” is extremely compelling. Suspended from the ceiling, over forty boats, many built by the artist, invoke feelings of transport, trade, travel, commerce and journeying.

Photo Courtesy of Ingrid Weaver

“For me, a ship is a vessel to carry you on a journey,” Locke said. “It involves trade, it’s about a hope for a better life. It’s a container for the soul.”

Locke’s imaginative reimagining of ships works well to both acknowledge the devastating effects of colonialism and to reclaim colonial imagery that is forward-looking and hopeful.

The last room of the exhibit features the video “The Tourists, 2015.” For this work Locke spent time on the HMS Belfast, a ship used in World War Two and the Korean War, which is now part of the Imperial War Museum.

In this video, Locke placed adorned mannequins throughout the ship, simultaneously acting as the ship’s crew but also, with their costumes and props, working as carnivalesque figures. This video is certainly disconcerting and another example of the reclamation of traditionally violent colonial objects in the name of critique.

Locke’s exhibit is one of the largest of his work, and it certainly makes quite a splash. Through the variety of mediums and the clever reclamation of colonial imagery as a means of critique, the exhibit shows the breadth and depth of Locke’s artistic capacities.

The exhibit runs until Jan. 19, 2020 at the Kemper Museum of Art in Kansas City. Admission is free to both the museum and the exhibit. Lunch at the museum’s Café Sebastienne is not required but is certainly tasty.