Standardized test form with answers bubbled in and a pencil, focus on answer sheet.

If you attended school in the United States public education system, chances are you had to labor through a standardized test or two during your time in primary and secondary education. As students, you are told that these tests are meant to measure the extent to which you have absorbed the course material and your ability to recall that information in a testing setting.

But what is the true purpose of standardized tests as they exist currently throughout American education? Do expansive institutions, like the state and federal government, along with private institutions, such as ACT and the College Board, mandate and create standardized tests solely for the benefit of the student?

In reality, standardized testing can be understood as a tool with multiple functions as well as many shortcomings.

To fully understand the effectiveness of standardized testing, you must first understand how the standardized test came about and what it is.

According to JSTOR Daily:

Many of the first widely adopted standardized school tests were designed not to measure achievement but ability. Intelligence tests, and similar assessments that grew in prominence in the early twentieth century, had an aura of scientific objectivity. The Army Alpha and Beta Tests, developed during World War I to sort soldiers by their mental abilities, became a model for the schools. Testing promised a way to identify kids who might go on to great things while avoiding wasting resources on ‘slow children.’… The most important test of ability, the College Entrance Examination Board—later renamed the Scholastic Aptitude Test, or SAT—began in the 1920s.”

Since the indoctrination of the standardized test into the U.S. public school system, they have increased in use and reliance. Dr. Donna Gardner, head of the William Jewell College education department, weighed in on how these tests are typically used.

“There [are] two kinds of standardized tests, broadly, norm-referenced standardized test and criterion-referenced standardized tests. Norm-referenced means you are making a comparison. So those kinds of tests rank students, you’re norming them against a population. Criterion-referenced tests measure your performance against a standard, against a [criterion],” Gardner said.

Gardner also noted that norm-referenced tests are largely not beneficial for instruction so much as they are used to simply compile statistical analyses and data about a student population.

Criterion-referenced tests, however, are very beneficial for instruction because they help determine where a child’s understanding is in relation to the things they are learning. It helps tell the teacher which specific areas a child needs to work on more.

This seems to cover the practical uses of standardized testing, but there is also another level of effectiveness on which standardized tests should be evaluated. Why do state structures mandate that we take standardized tests?

Dr. Kenneth Alpern, professor of philosophy Jewell, spoke about why the government mandates schools use standardized tests.

“Coming out of the disruptions of the 60s – where college campuses were a sort of challenge to power, challenge to government economics, social relations, sexual relations, everything – [Former Supreme Court Justice] Lewis Powell wrote a memo that was very influential that, in part, outlined how to denature the higher education as a source of destructive revolution [which] some of us might think [of as] some immaturity with a real chance of amazing creativity and imagination,” said Alpern.

Alpern elaborates that this memo – being the first expressing this sort of thinking – was used to help structure the education system so college students graduate with high debt and a need to find means to pay off loans to the state, which makes students, in a sense, subservient to them.

Alpern tied this back to standardized testing.

“Working within this system distorts all sorts of things that we have to do. That we have to prove to a bureaucracy that the money they are spending is in their terms, valuable to them. That we are turning out people compliant to the wishes of those in power,” Alpern said. “One way of thinking of standardized testing is as a way of enforcing that power, a way of trying to crush initiative, imagination, variation and the possibility of something really disruptive.”

Opposition to the argument that standardized testing is overall bad for the learning of students is dismissed by way of the other clearly beneficial purposes it serves such as the ones Gardner outlined. Alpern disagrees and cites the fundamental logic of standardized testing as corrupting in and of itself.

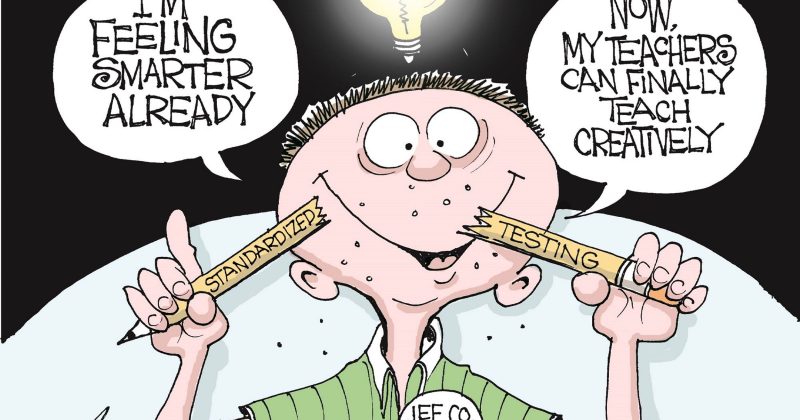

“To be standardized, to be regimented, is to be put into certain structures. Almost always at the college level I think that that regimentation kills the imagination and creativity that teachers and students have and develop together; it’s the magic of the classroom,” Alpern said.

Comic criticizing regimenting effects of standardized tests. Photo courtesy of News-Press

It is these sorts of oppositional statements that have sparked debate about the validity of standardized tests and whether or not they are fulfilling their intended roles. Further, it is important that school districts themselves answer this question due to the involved procedure of administering a standardized test.

Gardner represents the perspective of individual school districts.

“Standardized tests are a huge investment; they are very costly for public schools so the decision to use a standardized test is not [taken] lightly. If you are going to use a standardized test, then you are going to align your curriculum to these tests,” said Gardner.

When a curriculum is directed towards a specific set of questions on a test students will take at the end of the year, parents and educators begin to question the value of the education.

Alpern shares this question.

“There isn’t just one way of doing life and the nuances matter a great deal and when we try and metricize and quantify everything, we are distorting what the activity is,” Alpern said.

Our tools of education form how we conceptualize the prospect of learning. The current use of standardized tests necessarily directs how society experiences learning as a whole.

The question becomes “what do we need to fix?”

Many see some problem with the current testing culture of the U.S. Alpern traces the failure of standardized testing back to the desire of the state to indoctrinate people into the economic system of the U.S. by forcing a reliance on productivity by making it nearly impossible to seek higher education necessary to be competitive in the workforce without incurring massive amounts of debt.

Standardized tests are clearly not the sole cause of this system, but Alpern argues they are instrumental in seeing that the system functions.

Nevertheless, Alpern is a proponent of the way in which Jewell handles standardized testing.

“Some of the structural things that William Jewell has done is in the pursuit of real education, we have a core curriculum that you can’t standardize,” said Alpern. “At a high level we have ideas that are shown in the Capstone course that you must be able to critically reason about a moral issue that is of public concern that involves science so there are some of the components that have to be there, but lord save me from trying to standardize that so you can compare that across even the other sections, let alone other colleges.”

Photo courtesy of education.cu-portland.edu.